Recognizing Students and Schools for Civics Learning

To boost critical knowledge and skill building, some states offer diploma seals and school recognition programs.

With the narrowed focus on reading and math over recent decades, schools’ commitment to civics learning waned.[1] Predictably, students’ civic knowledge and skill levels reflected this underinvestment. Over the past three decades, eighth graders’ civics proficiency rates on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) ranged from 22 to 24 percent, the lowest among tested subjects except for US History.[2] State education leaders can turn this around through various means—from course mandates, to investment, to civic seals recognizing excellence in civics learning.

For example, students who took an eighth grade course focused on civics scored about 10 percent higher on NAEP, and they also benefited from engaging with primary-source materials, participating in simulations of democratic processes like mock trials, and debating and discussing contemporary issues.[3] But only five states require a stand-alone middle school civics course.[4]

For students in 28 states and DC, civics is a one-semester high school course, and 7 states require a year-long high school civics course. That leaves 15 with no requirement at all. Since 2018, 12 states have adopted new middle or high school course mandates, benefiting 700,000 students each school year.

For students in 28 states and DC, civics is a one-semester high school course, and 7 states require a year-long high school civics course.

Our organization, iCivics, leads a coalition of nearly 400 partners called CivxNow that recommends a panoply of state policy actions to improve civic learning. This menu includes a full year of high school civics, a semester in middle school, and designated instructional time in elementary school. CivxNow also recommends including civics in student and school accountability systems, funding for teacher professional development and high-quality instructional materials, and student programs.[5]

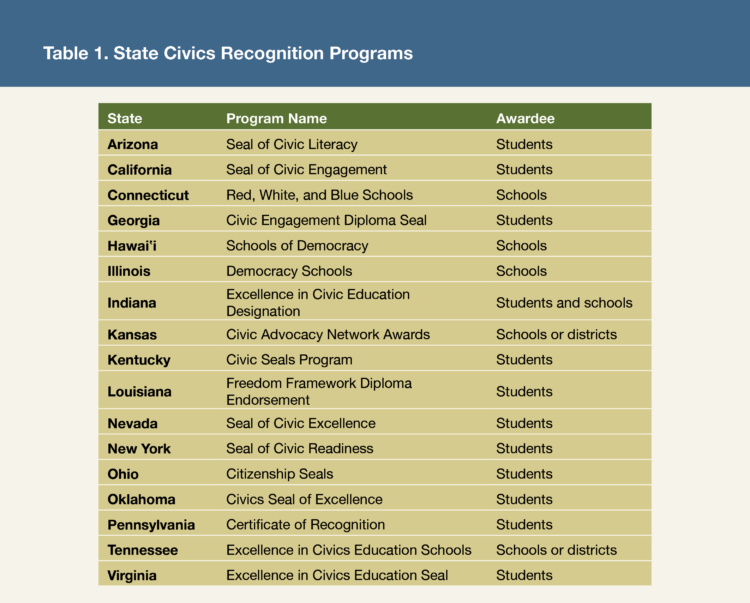

Acknowledging Excellence

Beyond mandates and money, states should encourage local education agencies (LEAs) and schools to acknowledge student participation and excellence in civics. Twelve states model this, employing myriad approaches under the banner of civic seals affixed to the high school diplomas of students who complete state requirements. Four more states recognize schools or districts for exemplary commitments to civics learning, as Illinois does through its longstanding, privately managed Democracy Schools initiative (table 1). In the spring 2025 state legislative sessions, five more states considered legislation to establish student civic seals programs: Alaska, Connecticut, Maryland, and Minnesota, and Missouri.[6]

Civics researcher Felicia Sullivan wrote more than a decade ago about “badges” as a pathway to incentivize deeper, more interactive civics learning without imposing an additional graduation requirement through imposition of a standardized test.[7] Students who experience such comprehensive civics learning opportunities are more likely to complete college and develop employable skills, vote and discuss current issues at home, be confident in speaking publicly and contacting public officials, and to volunteer and work with fellow citizens to solve community problems.[8]

Moreover, seals recognize skills that are attractive in potential employees and volunteers, moving beyond high school diplomas and college degrees. Finally, seals can legitimize the civic dimensions of skills applicable across the curriculum: writing, speaking, and group decision making. In a study of the early implementation phase of California’s Seal of Civic Engagement, researchers Erica Hodgin and Leah Bueso found that students who earned the seals expressed interest in earning recognition beyond the diploma, boosting resumes, and engaging in the community.[9]

Furthermore, project-based learning associated with civic seals programs, coupled with a reflection component, demonstrate the greatest fidelity to the pedagogical principles laid out in the national Educating for Democracy initiative (see article here).

A handful of states recognize schools or districts or both for exemplary commitments to students’ civic development. Traditional measures of school improvement that align with student achievement in literacy and numeracy will also help fulfill schools’ mission of promoting preparation for civic life.[10] Such measures encompass

- challenging curriculum;

- staff development, from recruitment through retirement;

- school leaders who embrace civics learning as a core tenet;

- a democratic school culture that honors student voice; and

- a reciprocal, mutually beneficial relationship between school and community.

Civic Seals. The dozen states that let students earn diploma seals for civics adopted diverse approaches.

To earn their state’s Seal of Civic Literacy, Arizona students must 1) pursue civics learning beyond the required senior government course (e.g., YMCA Youth and Government); 2) complete 30 hours of civic engagement activities, 10 of them civics specific; and 3) write a reflection on the civic seals experience.[11] The civic engagement activity component was modified in the past year to encourage more meaningful forms of service and to increase civic seals’ accessibility. As a result, seal recipients grew by a factor of 10 in a single school year.[12]

To earn California’s seal, students must

- engage productively in academic work;

- demonstrate civic knowledge, including the US and California constitutions;

- participate in one or more civic engagement projects;

- reflect upon civic knowledge, skills, and dispositions; and

- exhibit civic mindedness and a commitment to the classroom, school, and/or broader community.[13]

Indiana’s Excellence in Civic Education distinction will be available for students graduating from high school in 2029. It is paired with a school recognition program.

In order to earn Georgia’s Civic Engagement Diploma Seal, students must satisfy state high school social studies graduation requirements, pass the American Government Basic Skills Test, fulfill 50 hours of community service or extracurricular activities during high school, and complete a capstone portfolio demonstrating knowledge gained during the activities.[14]

The Kentucky Civic Seals Program requires

- a civic engagement project, which students select, design, and implement;

- knowledge of government and democratic principles through related coursework and assessments, which can include civic portfolios;

- demonstration of information literacy; and

- engagement in self-reflection on civic knowledge, skills, and commitments.[15]

The program is a partnership between the Kentucky Secretary of State and Kentucky Civic Education Coalition. Students who complete the seal receive a certificate from the secretary’s office. The coalition first attempted a legislative approach, which met with concerns about creating more bureaucracy.[16] When an administrative path through the state education agency also closed, it turned to Secretary of State Michael Adams, a willing partner from the outset.

Principal program architect Carly Mutteries characterized Kentucky seals as the “most grassroots of civic seals programs.” A pilot began in the 2023–24 school year, and an open call for applications started in 2024–25. The coalition offered minigrants to select schools to support some student projects. Seals projects are locally flexible and student driven. The program has attracted strong interest in elementary and high schools, and its K-12 span is another unique feature.

Louisiana’s Board of Elementary and Secondary Education approved the Freedom Framework Diploma Endorsement in April 2025. Beginning in 2026–27, students who earn mastery or above on the state civics assessment qualify for a civics seal and a red, white, and blue honor cord to wear at graduation.[17]

To qualify for the Nevada Seal of Civic Excellence, students must graduate with a GPA of 3.25 or above on a 4.0 scale, achieve 90 percent proficiency on the state’s civics exam, earn a satisfactory score on a provided “citizenship rubric,” complete a service learning project, and attain three social studies credits in high school.[18]

Students who earn New York’s Seal of Civic Readiness demonstrate “commitment to participatory government”; demonstration to colleges, universities, and employers of student completion of an action project; and recognition of the “value of civic engagement and scholarship.”[19] The students must gain civic knowledge through coursework, take an assessment, and participate in project-based learning and extracurricular activities.

Ohio students must earn two readiness seals to graduate, and citizenship seals are among the options. Seals criteria include satisfying both American History and American Government requirements, which encompass course performance or proficiency on end-of-course or equivalent AP exams.[20]

Oklahoma awards its Civics Seal of Excellence to students that earn a 3.0 GPA or higher in social studies courses, score 80 percent or higher on the US Naturalization Test, attain proficient or advanced levels on the College and Career Readiness Test for US History and Government, volunteer 75 hours or more of community service, and complete three civic engagement programs that the state education agency approves.[21]

Pennsylvania requires schools to administer a locally developed American history, civics, and government assessment during grades 7–12. Students earning a perfect score are awarded a certificate of recognition.[22] There is significant interest among Pennsylvania civics advocates and policymakers in establishing a more elaborate seals program akin to those of other states.[23]

The Excellence in Civics Education Seals is awarded to Virginia students who earn a B or better in American and Virginia history and American and Virginia government courses, have good attendance and no disciplinary infractions, and participate in 50 hours or more of community service or extracurricular activities or both (e.g., Boys or Girls State).[24]

School and District Recognition. Red, White, and Blue Schools are a partnership among Connecticut’s secretary of state, education department, and the Connecticut Democracy Center.[25] Each year two K-12 schools are recognized as Schools of Distinction, and one as Outstanding School. The latter carries a cash prize of $1,000. Winning schools also receive certificates.

Applying schools design student projects that promote community engagement and are assessed against a rubric. School systems may be recognized if elementary, middle, and high schools all participate. The Connecticut legislature is considering a bill this spring to also establish a student civic seals program starting with the Class of 2026.[26]

Launched by the Hawai‛i education department in 2023, Schools of Democracy are high schools that “… demonstrate dedication in preparing students to be active and informed participants in a democratic society.”[27] Recognized schools complete a months-long discovery process, providing evidence of students’ civic learning and engagement. The department plans to engage middle schools during the 2025–26 school year and pilot an elementary school program.

Despite inclusion in state code, nonprofits have administered Illinois Democracy Schools since their inception in 2005.[28] High schools earn recognition by completing a schoolwide civics assessment and later developing an improvement plan to strengthen civics learning opportunities and the democratic culture of the school (see article here).

Ninety geographically and demographically diverse high schools are now part of the Democracy Schools Network, a statewide community of practice that convenes annually. The current convener of the network, the Illinois Civics Hub, is piloting the program with elementary and middle schools to establish a K-12 civic learning continuum.

Kansas’s education agency recognizes K-12 schools with Civic Advocacy Network Awards.[29] Applications are based on evidence of schools employing promising civics learning practices.

The Excellence in Civics Education award goes to Tennessee schools and districts that incorporate civics learning opportunities across grades and subjects, develop foundational civic knowledge, offer teacher professional development opportunities and student resources, provide “real-world” civics learning opportunities from an extensive list, and implement a project-based assessment as required by a separate state law.[30]

Lessons Learned

There is continuing momentum behind state civic seals and school recognition programs. They have great appeal on the carrot side of the policy equation in a time of curricular crunches and fiscal constraints. They are arguably easy to adopt, though care must be taken as state agencies and LEAs turn toward implementation.

State civic seals and school recognition programs … have great appeal on the carrot side of the policy equation in a time of curricular crunches and fiscal constraints.

California provides the most instructive evidence.[31] During the pilot year for its seal program, 29 LEAs requested more than 5,000 seals. The next year, 65 LEAs requested seals for 10,000 students, or 2 percent of graduating seniors and 11 percent for the state’s LEAs.

While demographic analysis is unavailable, the program’s greatest uptake to date has been in districts adjacent to large urban areas, but not the urban districts themselves. Researcher Erica Hodgin and colleagues found that 67.8 percent of principals surveyed said district leaders had not informed them about the program, and 81 percent said teachers did not receive related professional learning opportunities.

Hodgin and Bueso profiled seven early-adopter districts.[32] They attribute their early successes to keeping equity and student access in mind. For example, students should be able to complete seal requirements during the context of the school day. Moreover, traditional measures like GPA, test scores, attendance, and disciplinary records present significant barriers to seal attainment.

Exemplar districts used the seal to raise the profile of civics learning and included a range of stakeholders, partners, and voices in program implementation. Students were key advocates for the seal program, and their voices are critical to program design and implementation.

Hodgin and Bueso also found staffing critical to districts’ success. Some districts identified building leads among faculty and granted them release from one class period. Also key is continued monitoring of equitable student access to civic seals for fear they will become another demographic sorting mechanism.

County offices of education helped spread the word about seals among districts, situating them within broader educational frameworks. County offices also provided related professional development opportunities for teachers and coached districts through implementation.

Hannah Rude, the Arizona Department of Education’s director of social studies, recommends that state agencies work closely with local and national partners in the civic education and engagement field to scale civic seals programs.[33] She sees civic seals as an opportunity to get non–honors track students involved in their communities. Rude hopes that higher education institutions begin honoring civic seals recipients with incentives like college credit and monetary rewards.

Conclusion

While civics learning was marginalized in an era of standardized testing and fiscal constraints, more states are incentivizing students, schools, and districts to foster civics learning and engagement opportunities through civic diploma seals and school recognition programs. With an eye toward equitable implementation, these early adopters illuminate pathways for other states to provide universal student access to a comprehensive K-12 civic education.

Andrea Benites is policy coordinator, Lisa Boudreau is state policy director, and Shawn Healy is chief policy and advocacy officer at iCivics.

Notes

[1] Paul G. Fitchett, Tina L. Heafner, and Phillip VanFossen, “An Analysis of Time Prioritization for Social Studies in Elementary Classrooms,” Journal of Curriculum and Instruction 8, no. 2 (2014); National Center for Education Statistics, “NAEP Report Card: 2022 NAEP Civics Assessment,” web page.

[2] National Assessment of Educational Progress, “NAEP Report Card: 2022 NAEP Civics Assessment,” web page (National Center for Education Statistics, 2022).

[3] Louise Dubé and Shawn Healy, in Valerie Strauss, “What the New Civics Test Scores Show Us, Besides the Obvious,” Answer Sheet perspective, Washington Post, May 11, 2023.

[4] CivxNow Coalition, “State Policy Scan,” web page.

[5] CivxNow Coalition, “State Policy Menu: A Guide to Strengthening Civic Education,” web page.

[6] CivxNow Coalition, “Pending Legislation in the States,” web page.

[7] Felicia M. Sullivan, “New and Alternative Assessments, Digital Badges, and Civics: An Overview of Promising Themes and Emerging Directions,” CIRCLE Working Paper #77 (Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement, Tufts University, 2013).

[8] The National Task Force on Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement, “A Crucible Moment: College Learning and Democracy’s Future,” report (Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities, 2012).

[9] Erica Hodgin and Leah Bueso, “Breaking New Ground with California’s State Seal of Civic Engagement: Lessons from Year 1,” study (Leveraging Equity and Access in Democratic Education Initiative, UCLA and UC Riverside, January 2022).

[10] Shawn Healy, “Essential School Supports for Civic Learning,” PhD dissertation (University of Illinois-Chicago, 2013).

[11] Arizona Department of Education, “Seal of Civic Literacy,” web page, update July 2024.

[12] Discussion with Hannah Rude, director of K-12 social studies, Arizona Department of Education, May 12, 2025.

[13] California Department of Education, “State Seal of Civic Engagement,” web page, reviewed February 12, 2025.

[14] Georgia Center for Civic Engagement, “Civic Engagement Diploma Seal Requirements,” web page.

[15] Carly Mutteries, Daniela DiGiacomo, and David Childs, “United We Stand: Examining Core Criteria for the Kentucky Civic Seal Program,” white paper (Kentucky Civic Education Coalition and Kentucky Council for the Social Studies, 2024).

[16] Discussion with Carly Mutteries, co-founder of Common Good, May 1, 2025.

[17] Louisiana Department of Education, “Louisiana Adopts New Diploma Endorsement to Recognize Excellence in Civic Education,” press release, April 9, 2025.

[18] Nevada Department of Education, “Seal of Civics and Seal of Financial Literacy Information and Criteria,” web page.

[19] New York State Education Department, “The New York State Seal of Civic Readiness Handbook,” last updated 2024.

[20] Ohio Department of Education and Workforce, “Citizenship Seal,” web page, modified February 4, 2025.

[21] Rick Farmer, “Oklahoma High School Students May Now Earn Civics Seal,” post (Oklahoma Council of Public Affairs, February 4, 2025).

[22] Pennsylvania Department of Education, “Act 35 Civics Toolkit,” web page.

[23] Discussion with Shannon Salter, April 23, 2025.

[24] Virginia Department of Education, “Diploma Seals,” web page.

[25] Connecticut’s Old Statehouse, “Red, White & Blue Schools,” web page.

[26] State of Connecticut General Assembly, Raised Bill 7009, An Act Concerning the Establishment of the Connecticut State Seal of Civics Education and Engagement, January Session, 2025.

[27] Hawaiʻi State Department of Education, “Kailua and Kalani High Schools Recognized as Hawaiʻi Schools of Democracy,” press release, February 5, 2025.

[28] Illinois Civics Hub, “Democracy Schools,” web page.

[29] Kansas State Department of Education, “Civic Engagement,” web page.

[30] Tennessee Department of Education, “Governor’s Civics Seal,” web page.

[31] Hodgin et al., “2022 Assessment.”

[32] Hodgin and Bueso, “Breaking New Ground.”

[33] Discussion with Hannah Rude.

Also In this Issue

The Challenges of Crafting Excellence in Civics and History for All

By Danielle Allen, Paul Carrese and Louise DubéThree authors of Educating for American Democracy revisit five aims depicted in their roadmap—and the miles to go.

The State of Youth Civic Engagement

By Jessica Sutter and Audra WatsonUnderstanding young people’s attitudes toward democratic participation can help states summon the resolve and the wisdom to strengthen civics learning.

Six Things State Leaders Can Do to Invigorate US Civics and History Learning

By Chester E. Finn Jr.Broad public agreement on what students ought to learn should propel their efforts, as should the lack of confidence in democratic institutions.

The Science of Experiential Civics

By Pamela Cantor MD, Fernande Raine and Susan RiversYoung people are wired for civics learning that connects them to their communities, builds their agency, and leverages relationships.

Recognizing Students and Schools for Civics Learning

By Andrea Benites, Lisa Boudreau and Shawn HealyTo boost critical knowledge and skill building, some states offer diploma seals and school recognition programs.

Preparing Students for Informed, Active Citizenship: Lessons from Illinois

By Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg and Mary Ellen DaneelsIllinois Democracy Schools are a key element of the state’s comprehensive approach.

i

i

i

i

i

i