The Challenges of Crafting Excellence in Civics and History for All

Three authors of Educating for American Democracy revisit five aims depicted in their roadmap—and the miles to go.

For many decades, public schools have failed to prepare young Americans for self-government, leaving the world’s oldest constitutional democracy in grave danger, afflicted by extremes of cynicism and nostalgia. But if state and local education leaders make nurturing informed, authentic, engaged citizens a priority now, they can change this trajectory.

We and our coauthors completed a national study of K-12 civics and history education in 2021.[1] Funded by the US Department of Education and National Endowment for the Humanities, we brought together experts from differing backgrounds and perspectives on what American citizenship education should be and do. All agreed that public schools were not supporting this subject sufficiently, and all saw the value in approaching the study from a national consensus so it would not be a progressive or a conservative program.

After collaborating with over 300 teachers, practitioners, scholars, and students, we released Educating for American Democracy: Excellence in Civics and History for All Learners.[2] The EAD report analyzed the current landscape and deficits and proposed a strategy for reform. A second, crucial piece was the accompanying “Roadmap to Educating for American Democracy.” We knew we should not attempt to recommend a national curriculum, given that states and districts make these choices in alignment with state-approved standards. But we thought state and other leaders could benefit from a content framework that laid out important themes alongside a coherent approach and pedagogy for addressing them, and we hoped such a framework could aid their efforts to improve citizenship education.

Four years after the EAD report and Roadmap were released, we see progress in promoting cross-ideological efforts to improve standards, curricula, and teaching in schools, with a number of districts aligning with the principles we lay out and several states working to improve learning standards. That said, the deficit America faced in 2021 was enormous—and still is.

Civic Crisis, Civics Deficit

We opened our report by stating that a healthy America requires “a reflective patriotism” in which We the People “unite love of country with clear-eyed wisdom about our successes and failures in order to chart our forward path.”[3] Since at least the 1990s, the very public disputes about the meaning of America and American history have tended to feature, as the dominant voices, severe and even cynical criticisms of America on the one side and, in response, a defensive or nostalgic patriotism about America’s greatness. The EAD report cites Alexis de Tocqueville’s description of Americans holding a reflective or considered patriotism, blending affection with critical analysis and argument, as embodying the high middle ground needed both in classroom education and in policy debates. We went on to lay out a concept of civics education we believe can be useful for assessing the presence, and adequacy, of civics in schools today (box 1).

Box 1.

A self-governing people must constantly attend to historical and civic education: to the process by which the rising generation owns the past, takes the helm, and charts a course toward the future. The United States is the longest-lived constitutional democracy in the world, approaching its 250th anniversary in 2026, an occasion that calls for both celebration and fresh commitment to the cause of self-government for free and equal citizens in a diverse society.

Education in civics and history equips members of a democratic society to understand, appreciate, nurture, and, where necessary, improve their political system and civil society: to make our union “more perfect,” as the U.S. Constitution says. This education must be designed to enable and enhance the capacity for self-government from the level of the individual, the family, and the neighborhood to the state, the nation, and even the world.

The word “civic” denotes the virtues, assets, and activities that a free people need to govern themselves well. When civic education succeeds, all people are prepared and motivated to participate effectively in civic life. They acquire and share the knowledge, skills, and dispositions necessary for effective participation.[4]

Content is the first essential element of an excellent citizenship education. The Roadmap lays out seven main themes rather than lists of facts, dates, figures in order to incorporate the second crucial element: an emphasis on inquiry. This approach can prepare citizens for the reality of pluralism, disagreement, and debate in our constitutional democracy, while also inspiring excitement and commitment for the adventure of self-government.

Design Challenges

Students need a balance between core civic knowledge and civic virtues—the skills and dispositions that enable citizens to commit to and operate a pluralistic constitutional democracy. The three civic virtues we emphasize are reflective patriotism, civil disagreement, and civic friendship. This approach to knowledge and civic virtues must be blended with an inquiry mindset in order to achieve five critical aims: (1) inspire students to understand and become involved in their constitutional democracy, (2) tell a full narrative of America’s plural yet shared story, (3) explore the need for compromise to make the democratic republic work, (4) cultivate civic honesty and patriotism so Americans can both love and argue about their country, and (5) teach history and civics both through a timeline of events and the themes running through those events.

Students need a balance between core civic knowledge and civic virtues—the skills and dispositions that enable citizens to commit to and operate a pluralistic constitutional democracy.

These five aims—we called them “design challenges”—capture the inherent tensions citizens must navigate, as well as the instructional challenges for civics educators. Across four grade bands, we braided history and civics learning to achieve the necessary blend of knowledge, civic virtues, and preparation for participation. The Roadmap completes this framework with layers of content questions—for teachers, curriculum designers, reviewers of state standards, and students. The Roadmap also attends to the realities of the digital age, fostering the civic duty to be careful about one’s sources for political or civic information and to be wary of echo chambers that limit independence of mind.[5]

Here’s an overview of what can be found in the EAD themes and challenges; summarized through the five design challenges.[6]

1. Motivating Agency, Sustaining the Republic. A constitutional democracy requires every new generation of citizens to understand it, use its forms of self-government, and develop the civic virtues needed to operate and sustain it. To develop these, students should be learning from those who have worked throughout the nation’s history to constructively build a more perfect Union—from the Founders and from exemplary figures such as Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Martin Luther King, Jr. This challenge asks, How can students appreciate the responsibility for self-government and the complexity of America’s forms of politics—and the reach of its global power—without feeling paralyzed or inadequate? How can citizens disagree about policy while remaining civic friends with Americans who think differently?

Students should be learning from those who have worked throughout the nation’s history to constructively build a more perfect Union.

American civic experience is tied to a particular place, and so civics education rightly also explores how the United States developed its physical and geographical shape; the complex experiences of harm and benefit that history has delivered to different portions of its populace; and how political communities form, become connected to specific places, and develop membership rules. A focus on the American landscape requires students to mull citizens’ contemporary responsibility to the natural world; to comprehend the religious, ethnic, and civilizational diversity that North America has attracted since the 15th century; and to take into account the realities of African slavery, Indigenous displacement, and the importance of groups of immigrants, including those from Central and South America, Asia, and Africa, as well as Europe.

2. America’s Plural yet Shared Story. Because governments derive “their just powers from the consent of the governed,” citizens have a right and a duty to control them. The US Constitution ensures consent through popular ratification (Article VI) and direct or indirect participation in all institutions. Crucial amendments expanded the circle of self-governing citizens, ensuring that “We the People” is animated by equality as well as liberty. This challenge asks, How can a more complete, plural story of the history and foundations of “We the People” also be the common story and shared inheritance of all Americans?

3. Celebrating and Critiquing Compromise. America is the first republic to declare its founding principles explicitly and the first to develop written constitutions. Big debates about government and reform launched its story—and still animate contending policy views today. The competing views in 1787 about what sort of government would best protect and assert the principles of the Declaration produced both The Federalist Papers and profound Anti-Federalist writings. Respect for debate and compromise is embedded in the Constitution, whose confident framers included an amendment procedure that has produced momentous changes to the American polity and elaborations of its founding principles. Certainly, civics learning should explore what compromises were made at the Constitutional Convention, how they were justified, and what unresolved business was left for later generations.

Respect for debate and compromise is embedded in the Constitution, whose confident framers included an amendment procedure that has produced momentous changes to the American polity and elaborations of its founding principles.

4. Civic Honesty, Reflective Patriotism. The revolutionary American spirit, across 250 years, continually presses: how to ensure consent of the governed while sustaining the ordered liberty that secures citizens’ rights equally while securing the common good? Calls for amendment immediately after the Constitution was born led to the Bill of Rights. In the aftermath of the Civil War, the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments extended protection to formerly enslaved Black Americans. When President Lincoln called for “a new birth of freedom,” was this a refounding? This question percolates through the progressive and civil rights eras and beyond. Do such changes extend founding principles or break from them? How does the nation balance civic honesty with reflective patriotism, encourage study of America’s failings without indulging cynicism, and appreciate our founding while admitting its imperfections?

5. Balancing the Concrete and the Abstract. America began precariously but became consequential. In President Washington’s Farewell Address, he articulated a strategy that sought independence yet took an ethical stance. The Monroe Doctrine extended that independence, asserting it for the Western Hemisphere. Can a 21st century superpower secure its interests and affirm ideals of justice? As the United States expanded across a continent then struggled to balance economic and military might with principles, it sometimes chose engagement and at others avoided adventurism. It led the defeat of Nazi and Communist totalitarianisms. As history marches on in the 21st century, Americans now are divided on principles and strategy as they cope with the reality of multiple great powers in the world. Should the United States seek only its national interest, avoiding entanglements, or should it lead the free world and a rules-based order? Historical and civics learning, blending concepts with cases, helps students understand and debate these views, assessing whether prior successes can guide current choices.

An interbedded theme explores today’s polarized terrain for civic participation and civic agency. It investigates how competing historical narratives shape current political arguments, how values and information shape policy arguments, and how the American people continue to renew or remake in pursuing the fulfillment of the promise of constitutional democracy.

We encourage educators to address contemporary civic topics, with guidance on how to navigate this challenging terrain. Breakdowns of civil discourse reflect the absence of a common ground—for both civic knowledge and civic virtues. If they dig deeper, can civics educators and learners reach shared views that unite most Americans? Whether the topic is technology, youth mental health, current events, issues of identity and inclusion, taxes, immigration, freedom of religion, or guns, can educators help youth listen for understanding and seek productive pathways for problem solving in a pluralistic democracy?

We encourage educators to address contemporary civic topics, with guidance on how to navigate this challenging terrain.

Lessons Learned from Early Adopters

Districts, teachers, students, and families are looking for resources to teach civics and history in a way that inspires students to become informed, engaged members of America’s constitutional democracy. There are pilots aligned to the EAD framework in 14 states.[7] We offer two examples in which students in classrooms with aligned curriculum enjoyed richer experiences and demonstrated meaningful growth in civic knowledge, skills, and dispositions.

In 2022, educational nonprofit iCivics produced an inquiry-based, primary source–rich, project-embedded US History I curriculum for eighth grade students called Through Inquiry. The free, high-quality curriculum has been piloted and researched in 10 school districts across 10 states, supporting 130 teachers and benefitting 12,000 students.[8] In 2023, Harvard’s Democratic Knowledge Project published a year-long eighth grade civics curriculum, “Civic Engagement in Our Democracy,” (discussed further below) which is being used in six states.[9]

In these classrooms, students learn to support a claim with evidence and reason by engaging in deep conversation with their peers; asking questions and collaborating to draw conclusions; moving around the classroom through strategies like gallery walks (circulating to interact with different information displays and resources) and jigsaws (a student gathers knowledge on one piece of a larger topic then collaborates in a group to piece together a larger view); exploring content through a variety of activities and media; and demonstrating learning in a variety of ways, from poetry to art to infographics.

In these [iCivics] classrooms, students learn to support a claim with evidence and reason by engaging in deep conversation with their peers.

“We do more interactive stuff in groups,” a Santa Fe student said. “In other classes, we normally just write down stuff. Here we involve more people. When we gather information, we get different points of view from different students.” These learning experiences create what one implementing teacher calls “a critical thinking mindset.” Before iCivics, her students “would just copy from the text and apply it. Now they have to read and give me an opinion.”

Ongoing research by the Civic Engagement Research Group at the University of California, Riverside also points to promising impacts on student engagement and learning. Students report at higher levels than their peers in non-iCivics classrooms that they had examined the causes and effects of important events in US History and that they compared and evaluated different points of view about the past. This finding brings to mind William Faulkner’s line that the past is never dead, it is not even past: American citizens and aspiring citizens need to understand the diverse views about major events, including arguments about facts versus narratives, not least given the reality that these competing views likely are shaping current civic realities and debates.

Harvard’s Democratic Knowledge Project published “Civic Engagement in Our Democracy,” a year-long eighth grade civics curriculum that seeks to help students “identify what they value, deepen what they understand, and develop what they can do to be self-caring, reciprocal, and self-confident changemakers.”[10] The online grade 8 curriculum platform for educators has over 2,000 users, with approximately one-third in Massachusetts. During the 2024–25 school year, 21 schools in 13 local education agencies (LEAs) in Massachusetts participated in the curriculum implementation support and professional learning program, DKP Launch, reaching 38 teachers and over 2,000 eighth grade students. The program will expand to add 54 more schools for the 2025–26 school year, reaching a total of 75 schools from 38 local education agencies and 145 teachers, impacting over 9,000 students across the state annually. In one assessment conducted by DKP, by the end of their eighth grade year students outperformed Massachusetts 25-year-olds on a combined measure of civic knowledge, civic self-confidence, civic self-care, and civic reciprocity.[11]

Advice for State Leaders

State leaders can use our work on Educating for American Democracy to evaluate their state’s civics education policies. We understand that the following recommendations make for a challenging list, given the current preservice preparation of many civics and history teachers in schools and the relatively lower priority for citizenship education in the current environment. But these are exactly the kinds of deficits that must be redressed if public schools are to improve their commitment and capacity to achieving this fundamental civic mission. We recommend the following:

- setting ambitious goals to ensure that all students have access to opportunities for excellent civics learning;

- adopting aligned social studies standards;

- supporting educator professional development by building networks across LEAs and by promoting preservice civics learning;

- requiring training as part of educator preparation or licensure requirements;

- requiring civics learning plans from LEAs;

- publishing civics learning plans to allow comparisons and assessments of progress;

- integrating the civics learning plan data within state accountability systems as a component of school performance indicators; and

- accrediting schools for excellence in civics learning.[12]

Adopting aligned standards is paramount.[13] State education leaders should use their standards revision processes to improve content rigor and depth. These implementation recommendations for the EAD Roadmap are the consensus work of CivxNow, the nation’s largest cross-partisan coalition working to prioritize civics education, which developed this policy “menu” as well as a continually updated state policy scan to track proposed legislation and policy changes across the United States.[14]

State education leaders should use their standards revision processes to improve content rigor and depth.

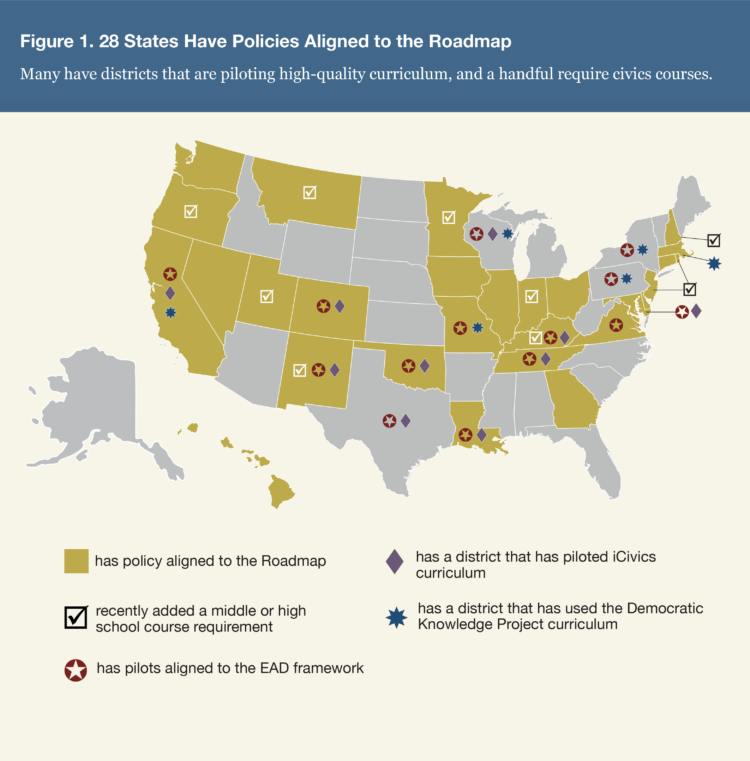

Since the Roadmap was released, 28 states have adopted over 40 aligned policies (see map).[15] These policies range from civics course requirements to civic seals, from funding for professional learning to state civics commissions. In the 10 states with new middle or high school course requirements, nearly half a million students are estimated to benefit annually.[16] In spring 2025, there were 181 bills in 44 states concerning K-12 civics; 72 percent aligned with CivxNow’s state policy menu.[17]

Because there are too few places where reasonable discussion and shared inquiry unfold in America, K-12 classrooms can and should be epicenters to renew civil dialogue, civic friendship, and practices of self-government. We hope state education leaders will reach out to us for partnership in renewing the reflective patriotism, civics education, and strong civic culture that American youth—and all its citizens—need.

Danielle Allen is the James Bryant Conant University Professor at Harvard University, director of the Allen Lab for Democracy Renovation, and director of the Democratic Knowledge Project-Learn. Paul Carrese is a professor at Arizona State University’s School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership. Louise Dubé is CEO at iCivics.

Notes

[1] Our EAD co-authors (with affiliations at the time of publication) are Jane Kamensky, Harvard University; Kei Kawashima-Ginsburg and Peter Levine, Tufts University; and Tammy Waller, Arizona Department of Education.

[2] Educating for American Democracy: Excellence in History and Civics for All Learners, report (iCivics, 2021). The EAD report discusses at pp. 9–10 the reduced priority and time for history, civics, and social studies in schools and the related absence of consensus about appropriate content for these subjects.

[3] Educating for American Democracy, 2.

[4] Educating for American Democracy, 9.

[5] A further rationale for prioritizing the renewal of civics education is that a world shaped by generative AI bots will require more background knowledge—not less—to evaluate whether what AI tools presents is accurate or helpful. To prepare students for this world, it is imperative to integrate an approach of raising deep questions and design challenges in every classroom.

[6] The seven EAD themes are 1. Civic Participation; 2. Our Changing Landscape; 3. We the People; 4. A New Government & Constitution; 5. Institutional & Social Transformation; 6. A People in the World; 7. Contemporary Debates & Possibilities.

[7] These states have EAD-aligned pilots: California, Colorado, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Missouri, New Mexico, New York, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and Wisconsin.

[8] The following states have pilots with iCivics’ “Through Inquiry: United States History, Beginnings to 1877,” (website): California, Colorado, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, and Wisconsin.

[9] The Harvard Democratic Knowledge Project curriculum is being used in California, Massachusetts, Missouri, New York, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

[10] Democratic Knowledge Project, 8th Grade Curriculum, web page (2023 version, piloted beginning in 2019).

[11] See also Natalie Sew, Adrianne Billingham Bock, and Danielle Allen, “Creating Student Leaders through Civics,” Phi Delta Kappan 105, no. 8 (2024-05): 26–31.

[12] Educating for American Democracy, “Stakeholder Brief for State Policymakers,” brief; see also CivxNow, “State Policy Menu: A Guide to Strengthening Civic Education,” web page.

[13] Fordham Institute’s 2021 review of state standards presents a well-respected, widely adopted review of the quality of state history and civics standards. The principles that animate Fordham’s review and Educating for American Democracy are directionally aligned, and states that adopt policies and standards that align with our framework will have a greater likelihood of meeting the criteria for rigor and depth on which Fordham bases its evaluation. Jeremy A. Stern et al., “The State of State Standards for Civics and US History in 2021,” report (Fordham Institute, June 2021).

[14] CivxNow, “State Policy Scan,” web page.

[15] These states include California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Utah, Virginia, and Washington.

[16] These states include Indiana, Kentucky, Minnesota, Montana, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, Oregon, Rhode Island, and Utah.

[17] CivxNow, “Pending Legislation in the States,” web page.

Also In this Issue

The Challenges of Crafting Excellence in Civics and History for All

By Danielle Allen, Paul Carrese and Louise DubéThree authors of Educating for American Democracy revisit five aims depicted in their roadmap—and the miles to go.

The State of Youth Civic Engagement

By Jessica Sutter and Audra WatsonUnderstanding young people’s attitudes toward democratic participation can help states summon the resolve and the wisdom to strengthen civics learning.

Six Things State Leaders Can Do to Invigorate US Civics and History Learning

By Chester E. Finn Jr.Broad public agreement on what students ought to learn should propel their efforts, as should the lack of confidence in democratic institutions.

The Science of Experiential Civics

By Pamela Cantor MD, Fernande Raine and Susan RiversYoung people are wired for civics learning that connects them to their communities, builds their agency, and leverages relationships.

Recognizing Students and Schools for Civics Learning

By Andrea Benites, Lisa Boudreau and Shawn HealyTo boost critical knowledge and skill building, some states offer diploma seals and school recognition programs.

Preparing Students for Informed, Active Citizenship: Lessons from Illinois

By Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg and Mary Ellen DaneelsIllinois Democracy Schools are a key element of the state’s comprehensive approach.

i

i

i

i

i

i