Weighing the Value of Industry-Based Certifications against Their Costs

A study of Texas’s move to offer bonuses and add accountability measures for attainment reveals some unintended consequences.

State policymakers’ efforts to ensure that high schools prepare all their graduates for postsecondary education and the workforce intensified over the last decade. This surge of attention reflects multiple pressures: graduates struggling to navigate a shifting labor market,[1] critiques of the “college for all” paradigm,[2] and growing skepticism about the rising costs and uncertain returns of higher education.[3] In response, many state education leaders have embedded college and career readiness (CCR) measures into state accountability systems. Some, like Texas, have also significantly incentivized students’ attainment of industry-based certifications (IBCs) while in high school.

Career and technical education (CTE) has long been a central strategy for equipping students with marketable skills.[4] During the past decade, CTE has been linked to a CCR strategy rising to prominence: ensuring students earn IBCs before they graduate.[5] Businesses, industry groups, or state-level certifying entities confer IBCs to students who have demonstrated competency in their domain of study. Although IBCs are distinct from the completion of CTE coursework, they are typically embedded in CTE programs at both the K-12 and postsecondary levels.[6] For instance, students might pursue a certified veterinary assistant license in an agriculture CTE program or an Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) certification in a construction CTE program.

Career and technical education has long been a central strategy for equipping students with marketable skills.

The logic of IBCs is that coursework alone may only weakly signal to employers that prospective employees possess the knowledge and skills to perform particular job functions. Additionally, licenses in fields such as education, health care, and human services may be required before one can be employed as a childcare provider, certified nurse assistant, or cosmetologist, respectively. IBCs may therefore serve as skill-signaling or formal screening mechanisms, depending on the IBC and occupation.

Coursework alone may only weakly signal to employers that prospective employees possess the knowledge and skills to perform particular job functions.

Yet as the number and variety of certifications multiply, so too do questions about their true value. Do IBCs actually open doors to meaningful employment or further education? Or do they risk becoming checkboxes within state accountability systems, diverting resources away from deeper learning experiences?

Embedded in Accountability Systems

The increasing prevalence of IBCs in high schools arose partly from federal and state policy reforms that incorporate CCR into state accountability plans and funding, with financial incentives for schools based on students’ receipt of IBCs included in some policies.[7] In 2015, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) required states to incorporate CCR components into state accountability plans.[8] By 2023, at least 16 states had begun using IBC receipt as an indicator in their ESSA plans.[9] Perkins legislation in 2018 made attainment of recognized postsecondary credentials a core accountability indicator, and at least 22 states chose IBC attainment as their Perkins indicator.

The increasing prevalence of IBCs in high schools arose partly from federal and state policy reforms that incorporate CCR into state accountability plans and funding.

Simultaneously, there has been a movement toward “skills-based hiring,” with skills often signified through nontraditional credentials such as IBCs.[10] Large corporations such as Amazon, Google, and Microsoft have removed degree requirements for many of their jobs, often replacing them with certifications they have developed.[11] Credential Engine, an initiative supported by the Lumina Foundation and JP Morgan Chase, has documented over 1.8 million distinct credentials available in the US economy.[12]

IBC Policy in Texas

Texas offers a compelling case study. Between 2017 and 2023, the share of high school graduates earning an IBC in Texas increased tenfold, from 3 to 33 percent.[13] This expansion was not incidental. The Texas legislature directed the Texas Education Agency to add IBCs to the college, career, and military readiness (CCMR) indicators in its school accountability system in 2017 and to publish a list of approved IBCs.[14] Since 2019, Texas schools have received CCMR outcomes bonuses when their students meet specific indicators, with $186 million distributed in 2021 and $197 million in 2022.[15] Schools receive bonus funds for students earning IBCs under the career-ready criteria, whereas students must enroll in a postsecondary institution for schools to receive bonus funding under the college-ready criteria.

While research has linked both CTE participation and earning IBCs to positive education and workforce outcomes like high school graduation, college enrollment, and short-term wage returns,[16] the explosion of nontraditional credentials has raised questions about their value and prioritization in state and federal education policy. In our study of IBC implementation in Texas, we explored these questions. We derived insights into the benefits and trade-offs of credentialing by talking to students and educators, as well as through quantitative analyses of the postsecondary outcomes associated with IBC receipt.

The explosion of nontraditional credentials has raised questions about their value and prioritization in state and federal education policy.

Certification on the Rise and Also Misalignment

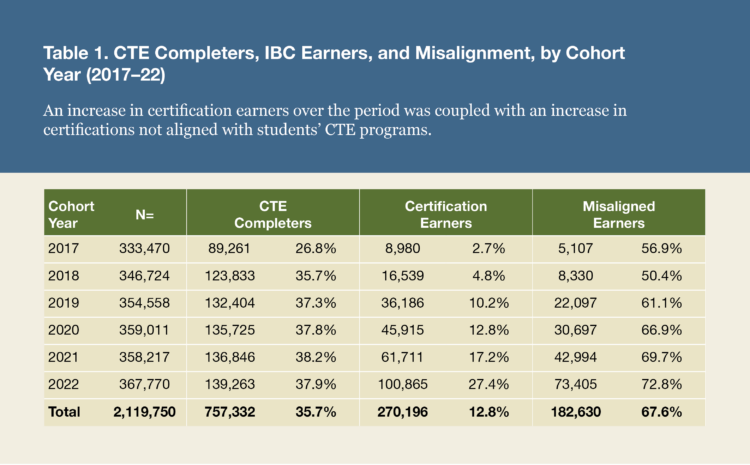

Our quantitative analyses drew upon a sample of more than two million students who graduated from Texas high schools between 2017 and 2022. In this period, 36 percent of students completed three or more CTE classes in the same subject area. We refer to these students as CTE completers. The rate increased sharply between 2017 and 2018 but has since remained roughly constant. In comparison, the rate of students earning any IBC increased dramatically over the six-year period, from 3 percent to 27 percent of students.

But the rate of students who earned IBCs that were misaligned increased from 57 percent to 73 percent of certification earners (table 1). We define a misaligned IBC as one earned outside the subject area of the CTE program a student completed—for example, when an education program completer earns a certified veterinary assistant license.

In other work,[17] we expand on the prevalence of this CTE-IBC misalignment, which we term curricular-credential decoupling. It suggests schools may be using IBCs to game the accountability and funding systems by letting students meet CCR requirements in a superficial way. When students earn certifications disconnected from their studies or career goals, the costs are borne at multiple levels:

- students waste time and energy preparing for and taking certification exams,

- teachers waste preparation and classroom time teaching IBC content or test-taking skills, and

- school, district, state, and federal resources are wasted in selecting, equipping, funding, and administering exams that provide no value to students.

Additionally, related research suggests not only that there is a limited relationship between IBC receipt and labor-market needs[18]—where students may be earning credentials that do not actually smooth entry into in-demand fields—but also that the majority of IBC earners were neither enrolled in a major nor employed in an industry after high school that matched their IBCs.[19] Such misalignments further call into question the true value of these credentials.

Students See Value in IBCs

Intrigued by these findings, we then visited seven high schools to better understand student and educator perspectives on the value of IBCs. At each school, we engaged with a range of CTE students, CTE teachers, and other school staff, like counselors and administrators.

On net, students saw the value of their CTE coursework in preparing them to transition to postsecondary education or the workforce and framed IBCs as a beneficial add-on to those classroom experiences. “If I would have to go be a cop right now, I could be confident in riding along with someone and knowing what I’m doing in situations,” one law enforcement student said. Students believed that IBCs “would look really good on applications” and give them “a leg up in the real world” because the certifications “can put you ahead of somebody else who’s going for the same job and might not have those certifications.” Additionally, students saw both time and financial benefits to CTE courses and IBCs. As one noted,

If you didn’t have these classes in high school and you had to start out, you’d have to pay for it yourself. But because we’re in CTE classes, the school pays for all of the certificates and stuff and testing that we have to get. And so, it makes it easier for us to be already ahead in the career that we want to do.

Students mentioned some costs affiliated with completing both CTE and IBCs, but these trade-offs were framed as minimal in comparison to the benefits, and for IBCs specifically, the costs were not salient for most students.

Educators Are More Skeptical

CTE educators also see value in the coursework students complete, but they do not generally value the IBCs. In fact, educators said that including and emphasizing IBC exams dampens the value of CTE, and they equate the certification tests to the mandatory end-of-course exams required in many school accountability systems. They said IBC exams force them “to teach to the test,” shifting class time away from hands-on learning and projects—the very components that both students and teachers cite as the most valuable.

While students saw the IBCs as helping them meet their career goals, educators described truly valuable certifications as the exception rather than the norm and expressed a “sense of defeat” over which IBCs were available to students. CTE departments offer IBCs that are formally aligned to the course subject area, but there is a consensus among the educators with whom we spoke that few certifications actually make students marketable to industry right after high school.

While students saw the IBCs as helping them meet their career goals, educators described truly valuable certifications as the exception rather than the norm.

In determining which IBCs to offer in courses, educators said their hands were tied because the school or district “won’t pay for it if it’s not on [the state’s approved] list,” regardless of a certification’s potential value to students. They describe IBC selection as a negotiation, where parties “butt heads with what we think is going to provide the best value to the student educational-wise versus money and what they want in the curriculum.” One automotive technologies teacher expressed feeling

a sense of defeat. The IBC that they want me to teach has value, but it’s … not going to get the student to stand out to [employers] more. It’s just as simple as that. I know that. I came from the industry. The IBC that I [teach] is geared to another level, more down the line of being an owner.

Despite their misgivings, educators said they were obliged to “sugarcoat” the value of IBCs to students because of the salient CCMR environment. IBCs are a means for accomplishing school-level accountability goals, and many educators described the certifications as “just another thing we have to check off the list”—for graduation or accountability purposes. Because of the funding tied to accountability ratings and CCMR indicators, educators in some cases were even given a “list of students who [they] were responsible for certifying” by the end of the year from their school or district. Educators said the emphasis on CCMR metrics “makes or breaks a district for a grade, and these are things that are not best practice for kids.”

IBCs are a means for accomplishing school-level accountability goals, and many educators described the certifications as “just another thing we have to check off the list.”

The stakes are compounded by IBCs serving as metrics for incentive allotments or indicators of teacher performance, with several noting that the numbers are tracked and that school leadership expects them “to be doing better every year in terms of number of certifications.” This pressure on teachers can translate to pressure on students, with some high schoolers saying, “they definitely push it” and knowing that “the school wants everybody in CTE to graduate with at least one certification.” These tensions led one educator to summarize the dilemma bluntly: “Are we doing it for the kids, or have we turned into a business about school?”

Texas’s Investment in IBCs Is High

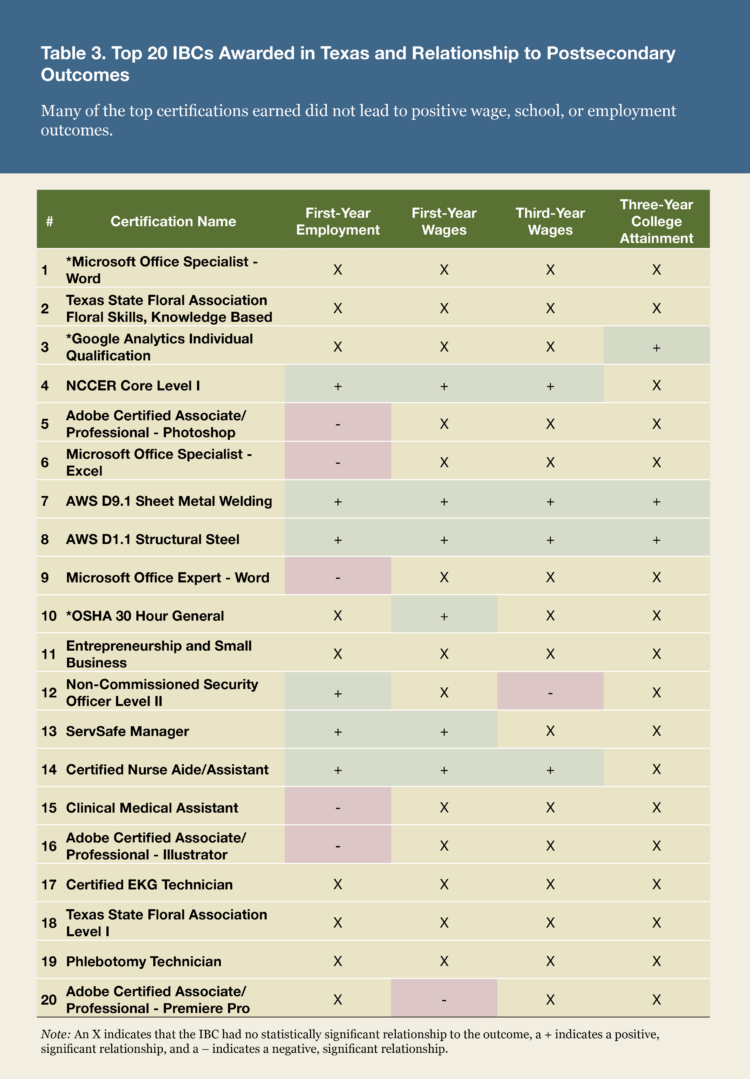

To better understand whether earning an IBC in high school gives students advantages in the labor market or in postsecondary education, we linked data on IBCs earned with students’ postsecondary outcomes. We synthesize the estimated value of the 20 most commonly earned IBCs in tables 2 and 3.

Columns indicate the number of each IBC that students earned from 2017 to 2022, the percentage of all earned IBCs that this number represents, the total cost of each IBC to the state (calculated by multiplying the number of IBCs earned by the per-IBC cost listed in state data), the percentage of all IBC spending this represents, the corresponding CTE field, the alignment rate (the percentage of each IBC earned by students who also completed three or more CTE courses in the same subject), and estimates from the statistical models. An X indicates that the IBC had no statistically significant relationship to the outcome, a + indicates a positive, significant relationship, and a – indicates a negative, significant relationship.[20]

Despite large financial investments from the state, few of the popular IBCs seem to actually improve students’ labor market and education outcomes. Between 2017 and 2023, students earned over 800,000 IBCs, at a cost to the state of more than $20 million in direct exam expenses (not including their portion of CCMR outcomes bonus investments). The 20 certifications in table 2 represent 78 percent of certifications earned and 74 percent of total costs, at about 650,000 and $15.3 million, respectively. Six of these IBCs have no significant associations with outcomes, including the two most popular ones, a Microsoft Word certification and a floral skills exam (table 3). This is not to say all IBCs are fundamentally useless. Students might pursue IBCs outside their CTE field of study as an intentional strategy to obtain a breadth of skills and knowledge, and some IBCs, like the certified nurse aide/assistant, show both a high alignment rate, relatively low program costs, and several statistically significant relationships to workforce outcomes.

Few of the popular IBCs seem to actually improve students’ labor market and education outcomes.

Asterisks indicate that an IBC has been or will be retired from the education agency’s approved list,[21] which is one strategy Texas has employed to ensure that the approved certifications prepare students for success. All IBCs previously on the approved list and any newly submitted IBCs are reviewed to determine if they are industry-recognized, attainable by a high school student, “portable,” and “capstone.”[22]

The most recent review process also introduced a three-tiered ranking system, which classifies an IBC as Tier 1 if it is “an in-demand certification directly aligned to a high-wage occupation,” Tier 2 if it is “directly aligned to an occupation that is either in-demand and high wage or high skill,” and Tier 3 if it is not in-demand, high wage, or high skill.[23] Fourteen of the active certifications in this table are Tier 2; both floral association exams and noncommissioned security officer level II are Tier 3. While this ranking system is a useful first step in categorizing IBCs’ value, to date, these ranks have not been incorporated into Texas’s accountability or funding formulas. However, changes to Texas’s CCMR credit requirements will require alignment of CTE course subjects and certifications for all future graduates.

Advice for State Leaders

While IBCs are supposed to add value to students’ college and career pathways, our findings suggest their actual economic benefits are limited. Some offer tangible advantages, but many commonly earned certifications fail to provide statistically significant benefits. While students largely view CTE coursework and IBCs as valuable, educators express much more skepticism, emphasizing the misalignment between IBCs and industry needs, and financial and curricular constraints that limit their effectiveness and detract from CTE learning. Further, the escalating misalignment suggests that education policy has created an environment in which schools are rewarded for helping students earn IBCs unrelated to their aspirations.

While students largely view CTE coursework and IBCs as valuable, educators express much more skepticism.

For state leaders, several principles emerge:

Incentive structures should weigh higher-value, higher-skill certifications more heavily than low-skill ones. Some states have implemented policies that provide more “points” for IBCs that require more education and training than others. For example, earning a license as a licensed vocational nurse requires far more coursework than a CPR certification. Although both count as health science IBCs, schools ought to be encouraged to support students’ completion of higher-level IBCs.

Funding and accountability credits should prioritize certifications directly aligned to students’ CTE programs of study. To dissuade schools from gaming the system by overprescribing easy-to-earn IBCs, policies could assign more points for aligned over misaligned IBCs or require IBCs to be earned in aligned CTE subjects.

States should equalize or subsidize the direct cost of IBCs to schools or districts so schools can offer more IBCs with recognized industry value. Educators shared frustrations that state or district priorities push them toward cheaper certifications, regardless of actual workforce value for students. States could consider equalizing the costs of individual IBCs within each “tier” or “point,” so that offering valuable certifications is not disincentivized. For example, certifications worth one point might have direct exam costs of $100 per student, whereas three-point certifications might cost $300 per student.

Regular review of the approved IBC list is essential. Auditing the list gives educators and industry groups opportunities to propose industry-valued certifications to be added and for the state to identify IBCs that provide little value to students or that are being overprescribed.

The central question remains: Which IBCs truly prepare students for meaningful college and career pathways, and at what costs? At their best, certifications provide students portable, industry-recognized skills that complement CTE coursework and strengthen pathways to employment. At their worst, they become hollow signals—absorbing scarce instructional time and public resources without delivering on their intended purpose. As states refine their policies, the challenge is not only to expand access to credentials but to ensure that they bridge students to actual opportunities.

Madison E. Andrews is a research associate, Kaitlin Ogden is a postdoctoral fellow, and Matt S. Giani is a research associate professor of sociology at the University of Texas at Austin.

Notes

[1] Anthony P. Carnevale, Stephen J. Rose, and Ban Cheah, “The College Payoff: Education, Occupations, Lifetime Earnings,” report (Georgetown University, Center on Education and the Workforce, 2013).

[2] James E. Rosenbaum, Beyond College for All: Career Paths for the Forgotten Half (Russell Sage Foundation, 2001); James Rosenbaum and Janet Rosenbaum, “The New Forgotten Half and Research Directions to Support Them,” A William T. Grant Foundation Inequality Paper (William T. Grant Foundation, 2015).

[3] Richard Fry, Dana Braga, and Kim Parker, “Is College Worth It?” report (Pew Research Center, 2024).

[4] Shaun M. Dougherty and Allison R. Lombardi, “From Vocational Education to Career Readiness: The Ongoing Work of Linking Education and the Labor Market,” Review of Research in Education 40, no. 1 (2016): 326–55.

[5] These are sometimes referred to as industry-recognized certifications or just industry certifications.

[6] Anthony P. Carnevale, Stephen J. Rose, and Andrew R. Hanson, “Certificates: Gateway to Gainful Employment and College Degrees,” report (Georgetown University, Center on Education and the Workforce, June 2012).

[7] Albert Y. Liu and Laura Burns, “Public High School Students’ Career and Technical Education Coursetaking: 1992 to 2013: CTE Statistics” (National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, November 2020); Advance CTE and College in High School Alliance, “The State of CTE: Early Postsecondary Opportunities,” report (Washington, DC, 2022).

[8] Donald G. Hackmann, Joel R. Malin, and Debra D. Bragg, “An Analysis of College and Career Readiness Emphasis in ESSA State Accountability Plans,” Education Policy Analysis Archives 27 (2019), https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.27.4441.

[9] Bryan Kelley, Lauren Bloomquist, and Lauren Peisach, “Secondary Career and Technical Education,” 50 State Comparison, Education Commission of the States, March 2, 2023.

[10] Joseph B. Fuller et al., “The Emerging Degree Reset,” report (Burning Glass Institute, 2022).

[11] María Mercedes Mateo-Berganza Díaz et al., A World of Transformation: Moving from Degrees to Skills-Based Alternative Credentials (Inter-American Development Bank, 2022), https://doi.org/10.18235/0004299.

[12] Credential Engine, web page.

[13] Matt S. Giani et al., “Curricular-Credential Decoupling: How Schools Respond to Career and Technical Education Policy,” EdWorkingPaper 25-1128 (Annenberg Institute at Brown University, 2025).

[14] Texas Education Agency, “Industry-Based Certifications,” web page.

[15] Texas Education Agency, “CCMR Outcomes Bonus Report Updates,” September 19, 2024.

[16] See, for example, Jim Lindsay et al., “What We Know About the Impact of Career and Technical Education: A Systematic Review of the Research” (American Institutes for Research, Career and Technical Education Research Network, 2024); Matt S. Giani, “How Attaining Industry-Recognized Credentials in High School Shapes Education and Employment Outcomes,” report (Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2022).

[17] Giani et al., “Curricular-Credential Decoupling.”

[18] Ben Dalton et al., “Do High School Industry Certifications Reflect Local Labor Market Demand? An Examination of Florida,” Career and Technical Education Research 46, no. 2 (2021.): 3–22.

[19] Giani, “Attaining Industry-Recognized Credentials in High School.”

[20] These results are a small selection of our findings, which can be read in full in our other work.

[21] Texas Education Agency, “Industry-Based Certifications.”

[22] Texas Education Agency, “Industry-Based Certifications for Public School Accountability,” Rule §74.1003.

[23] Texas Education Agency, “Industry-Based Certifications for Public School Accountability,” Rule §74.1003.

Also In this Issue

The Role of State Boards in Making Credentials’ Value Transparent

By Scott CheneyNot all credentials are created equal, so how will students and families choose?

Weighing the Value of Industry-Based Certifications against Their Costs

By Madison E. Andrews, Kaitlin Ogden and Matt S. GianiA study of Texas’s move to offer bonuses and add accountability measures for attainment reveals some unintended consequences.

Remaking Transcripts to Better Reflect Students’ Competencies

By Celina Pierrottet and Jon AlfuthState boards wanting to capture student mastery in new ways have many considerations to take into account.

Turning Graduate Portraits into Pathways

By Laura SloverNorth Carolina and Indiana are leading in the push toward teaching and assessing durable skills.

Deskilling the Knowledge Economy: Implications for Schools

By Brent OrrellTo foster students’ entry into the workforce, their schools will need to equip them with AI-complementary skills.

i

i

i

i

i

i