Deskilling the Knowledge Economy: Implications for Schools

To foster students’ entry into the workforce, their schools will need to equip them with AI-complementary skills.

As artificial intelligence (AI) platforms absorb routine tasks, entry- and mid-level knowledge workers in finance, business services, government, and health care face growing vulnerability to deskilling and displacement. The workers best positioned to thrive in this environment will be those who combine legacy technical skills, such as mathematics and coding, with AI literacy and more general capabilities including critical thinking, communication, and adaptability—skills that are essential for hybrid roles overseeing and managing AI systems.[1]

To better support students and schools during this transition, state boards of education should leverage state and regional labor market information systems and strengthen partnerships with workforce development leaders and employers to improve skill forecasting and curriculum development. They should also prioritize durable and portable credentials, support for families and early education in building foundational skills such as communication and adaptability, and expanded access to pathways of opportunity for disadvantaged and rural populations.

State boards of education should leverage state and regional labor market information systems and strengthen partnerships with workforce development leaders and employers to improve skill forecasting and curriculum development.

A Moving Target

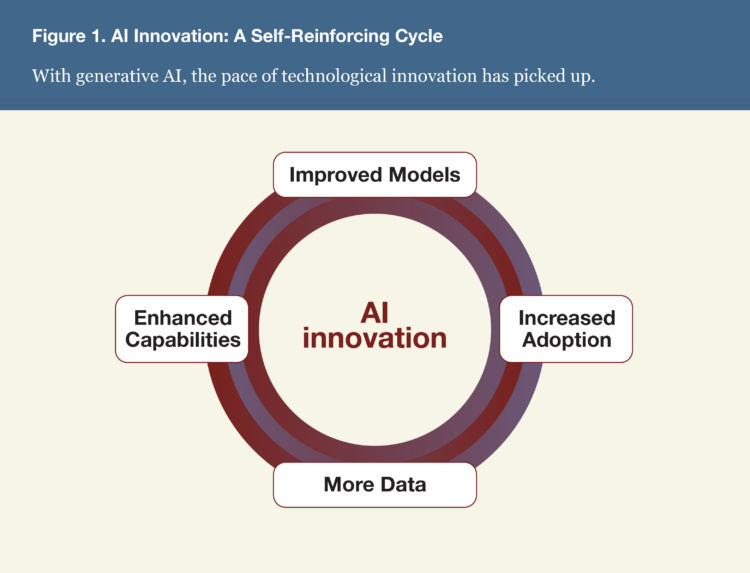

Forecasts of AI’s impact on jobs and skills are notoriously inconsistent. This is not a failure of the forecasters’ methods or effort; it reflects data challenges and, most critically, the speed and unpredictability of AI developments. AI operates on a recursive innovation cycle: Improvements generate more adoption, which produces more data, thus accelerating further improvements and at a pace distinct from previous technological developments. By the time predictions are made, they are already outdated (figure 1). Recursivity itself may accelerate as AI systems take on the characteristics of semi- or unguided self-improvement.

Rather than seeking precise estimates, policymakers—and state education leaders in particular—will find it more useful to track broader trends and apply them to today’s job market. By focusing on the contours of labor market change instead of exact numbers of job skills, state boards can position schools to prepare students for the opportunities and risks of the AI transition without becoming overprescriptive in a fast-moving environment.

Rather than seeking precise estimates, policymakers—and state education leaders in particular—will find it more useful to track broader trends and apply them to today’s job market.

The Stakes for Knowledge Workers

Like other advanced economies, the US economy is dominated by services, which account for nearly 80 percent of employment.[2] Within services, the most AI-exposed roles are “knowledge” activities—finance, insurance, business services, government, and health and social assistance—jobs filled largely by college-educated workers who process, manage, and interpret information.

AI systems excel at precisely these data management and interpretation functions. They effortlessly execute repetitive cognitive tasks and identify patterns within vast datasets at a scale unworkable for humans. As adoption spreads, the demand for many mid-level knowledge workers, who heretofore were responsible for such tasks, is likely to decline, echoing the deindustrialization of the late 20th century.[3]

As [AI] adoption spreads, the demand for many mid-level knowledge workers … is likely to decline, echoing the deindustrialization of the late 20th century.

US workers can expect the following:

- Up-or-out pressure. Some workers will upgrade skills to complement or supervise AI; others will be pushed into lower-paid jobs. Jobs likely to be replaced include customer service representatives, truck drivers, and computer programmers, whereas teachers, social workers, and electricians are among the most resilient roles.[4]

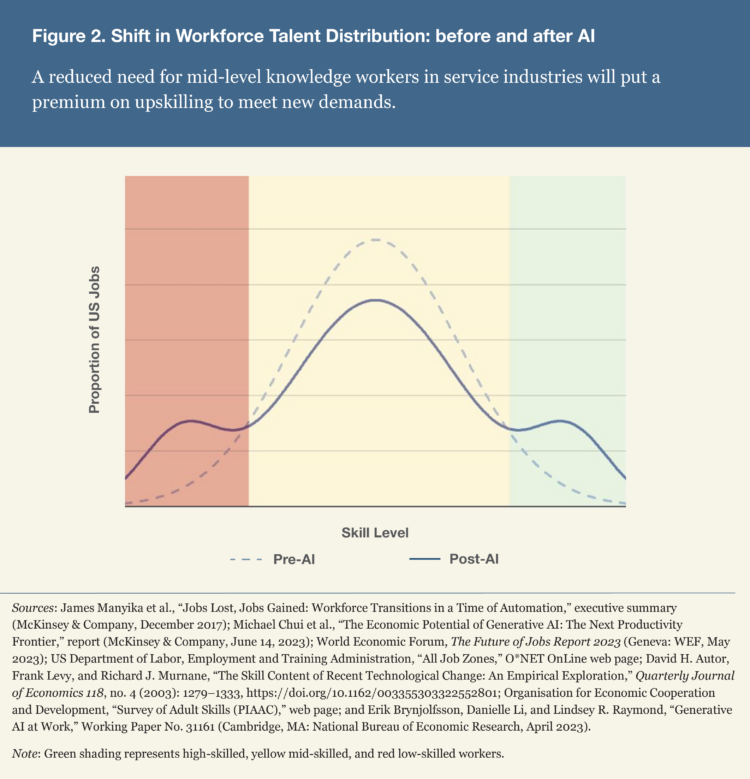

- Compression of middle-skill roles. Routine cognitive work will shrink, while demand will grow at the high and low ends of the distribution.

- New opportunities. Just as automation once created new industrial and service roles, AI will generate jobs analysts cannot predict—especially those blending technical fluency with human judgment (figure 2).

For state boards, this reality requires a shift: Schools must prepare graduates, not for the entry-level jobs of yesterday, but for immediate employment in hybrid, higher-value roles within an AI-infused workplace.

Lessons from Skills-Biased Technological Change

Skills-biased technological change theory explains how technological progress consistently raises demand for higher-order skills while eroding routine work. In manufacturing, robotics and information technology deskilled repetitive factory jobs, hollowing out middle-class employment.[5] Simultaneously, demand surged for college-educated workers in services and information-intensive roles.[6]

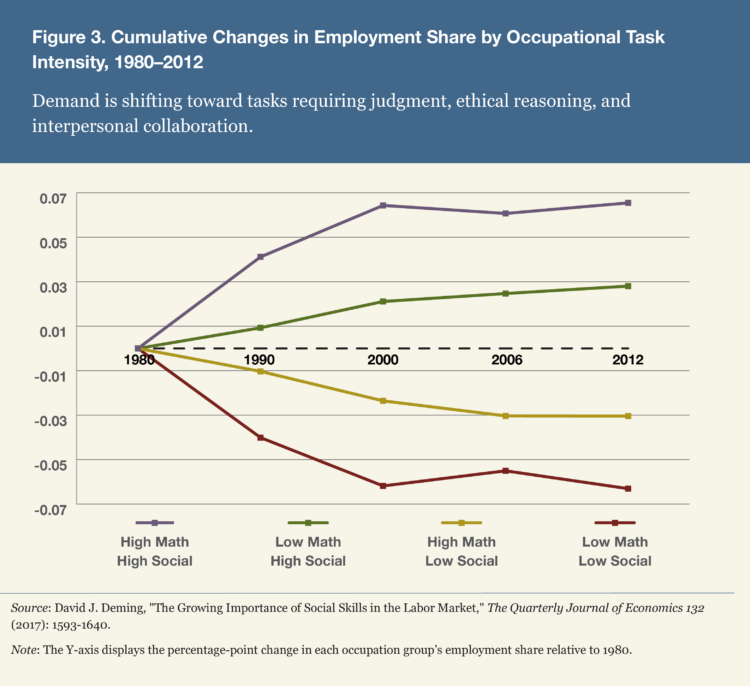

AI now extends this theory into the knowledge economy itself. Routine coding, financial analysis, claims processing, and scheduling can be automated. Demand is shifting toward tasks requiring judgment, ethical reasoning, and interpersonal collaboration (figure 3).[7]

Demand is shifting toward tasks requiring judgment, ethical reasoning, and interpersonal collaboration.

This trend is visible in IT employment. Basic coding tasks are increasingly automated, reducing opportunities for junior programmers. Meanwhile, experienced engineers who can integrate, supervise, and optimize AI systems remain in high demand.[8] The pattern mirrors past transitions: deskilling routine tasks, coupled with rising returns to advanced skills, and a growing premium on “soft” or noncognitive abilities.

For state boards, the implication is clear: The old ladder of skill development—where graduates climbed gradually through routine entry-level work to more-skilled work—is being transformed.[9] The logical implication of this reality is that educational institutions at all levels must now supply more of the scaffolding that early-career jobs traditionally provided.

AI’s Impact on the “Big Four”

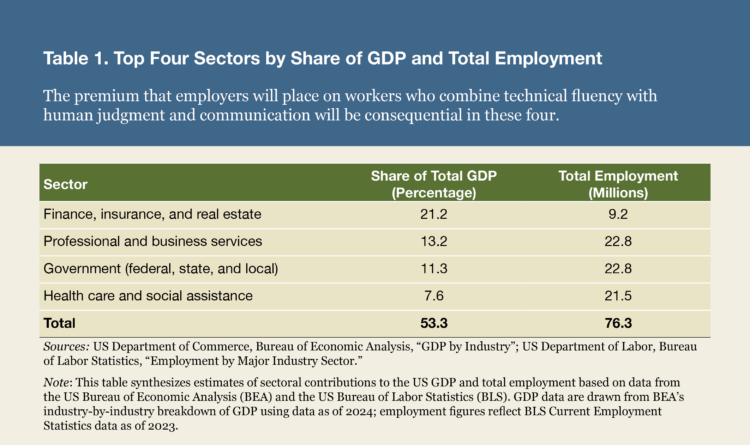

AI is rapidly reshaping the knowledge economy, with the sharpest effects in information-intensive fields where routine cognitive tasks are most exposed.[10] As automation compresses mid-level roles, demand is shifting toward hybrid jobs that combine technical fluency with human judgment and communication. Nowhere is this clearer than in the four top US service sectors (table 1), where AI is redefining both the risks and opportunities for the next generation of workers.

Finance and Insurance. AI already enhances risk assessment, fraud detection, and customer service. Routine roles in compliance monitoring and manual data analysis are declining. In their place, demand grows for the following:

- algorithmic traders and financial analysts fluent in AI;

- compliance specialists who understand bias, ethics, and regulatory implications; and

- relationship managers who can interpret complex insights and communicate with clients.

Business Services. In consulting, marketing, and HR, AI streamlines contract analysis, recruitment, and client communication. Entry-level support roles are shrinking, while demand rises for the following:

- AI-powered consultants and recruiters;

- strategists skilled in critical thinking, creativity, and storytelling; and

- professionals who can bridge technical capabilities with empathy and collaboration.

Government. AI supports tax processing, benefits administration, and smart-city planning. Clerical positions are declining, while opportunities grow in these jobs:

- AI-literate policy analysts and program managers;

- cybersecurity and digital governance specialists; and

- public engagement staff who explain AI-driven policies.

Health and Social Assistance. AI automates scheduling, billing, and diagnostic support. Administrative roles are at risk, but opportunities are expanding for these workers:

- health informatics specialists and technicians using AI-enhanced diagnostics;

- care coordinators bridging patient needs with AI systems; and

- counselors and assistants who combine empathy with AI tools for mental health and wellness.

Across sectors, the pattern is consistent: Routine cognitive work is squeezed, while hybrid roles blending technical fluency with human-centered skills expand.

Addressing the Real Skills Gap

AI’s impact will not be evenly distributed. As with past technological transitions, the most adaptable, well-rounded workers who are equipped for continuous, rapid-cycle learning will prosper, while those with narrower skill sets are more likely to face displacement. The “compression” of middle-skill jobs is likely to widen inequality unless schools, families, and communities intervene.

The “compression” of middle-skill jobs is likely to widen inequality unless schools, families, and communities intervene.

This inequality underscores three imperatives for state boards:

- Prepare all students for AI fluency, and not just those in high-income or metropolitan-based districts.

- Engage with other divisions of government to highlight the importance of early social and literacy skills. Teamwork, resilience, and problem solving—which are decisive for long-run adaptability—are built on a foundation of stable early family life and learning and are the precursors of learning readiness.[11] These skills have always been important (and according to employers in chronic low supply), but AI further heightens the need to develop them. Schools cannot solve or remediate these challenges by themselves; working on broad prevention strategies that incorporate human and social services as well as education is essential.

- Foster access to broadband, advanced coursework, and work-based learning opportunities in rural and underserved communities.

Policy Priorities for State Boards

Embed AI Literacy across the Curriculum. AI is not a specialized subject; it is a basic skill alongside reading and math. To some degree, AI will democratize knowledge and skills, allowing students to supplement and build their abilities on an accelerated basis. Students should use AI tools in science, English, history, and math—not as shortcuts, but as platforms for critical evaluation. Teacher preparation must include AI training, and assessments should measure both technical fluency and judgment.

Redefine Graduation Requirements. States may wish to incorporate AI readiness in high school graduation requirements. Diplomas should certify readiness for AI-influenced work. Boards could require at least one industry-recognized credential that is durable, portable, stackable, and employer-recognized. Examples include AI-augmented data analysis, digital ethics, or project management.

States may wish to incorporate AI readiness in high school graduation requirements.

Modernize Career and Technical Education. CTE programs must evolve beyond narrow occupational training to emphasize adaptability, collaboration, and human-AI teamwork. States like Utah have piloted AI-focused career pathways that blend technical and leadership skills, producing graduates with stronger advancement opportunities.[12] Additionally, the economy continues to require large numbers of skilled tradespeople—electricians, HVAC installers, welders—whose work remains difficult to automate.[13] CTE modernization should therefore support both emerging AI-aligned pathways and the durable trade occupations that remain foundational to local and regional economies but will still require AI literacy and fluency to greater or lesser degrees.

Foster Access for Disadvantaged and Rural Students. Boards must address digital divides by advocating for investments in broadband, regional technology hubs, and mobile labs. Partnerships can provide underserved districts with access to AI tools and mentorship. North Dakota’s broadband-enabled apprenticeships offer a model.[14]

Boards must address digital divides by advocating for investments in broadband, regional technology hubs, and mobile labs.

Promote Lifelong Learning. The AI economy will require constant reskilling. Boards can build articulation agreements linking high school, community colleges, and universities, and expand online microcredentials accessible to working adults. Stanford University Center on Longevity is engaged in a long-term project to improve preparation of students for lives of continuous learning.[15]

Support Resilience as the Foundation for Learning. The paradox of AI is that as machines take on more cognitive load, human capabilities—resilience, empathy, ethical reasoning—become more valuable. These traits are shaped in childhood. State boards should support early childhood education and family strengthening programs, mentoring of K-12 students, and wraparound services that buffer against trauma and instability, laying the foundation for ready-to-learn students and adaptable adults. Some of the best-documented evidence of the effectiveness of these early interventions can be found in programs like the Nurse Home Visiting Program and the Portland, Oregon-based nonprofit Friends of the Children.[16]

The paradox of AI is that as machines take on more cognitive load, human capabilities—resilience, empathy, ethical reasoning—become more valuable.

Partnerships with Industry

One of the perennial challenges state leaders face in easing the school-to-work transition is understanding employers’ current needs. Better durable skill preparation can help. The other half of the solution is regular engagement with local industries, businesses, and business coalitions to update educators’ understanding of how technology is reshaping skill needs and opening up on-the-job learning opportunities. Boards should formalize partnerships with employers to

- convene regional industry councils to identify emerging skills;

- expand internships, apprenticeships, and job-shadowing opportunities; and

- provide access to AI platforms, software, and mentorship.

These collaborations can ensure that credentials reflect real demand and give students exposure to AI-enhanced workplaces.

Data and Forecasting

A persistent need is the lack of timely, granular data on how AI adoption is reshaping skills. Current labor market information is retrospective and too often national in scope. State boards need forward-looking, local data to guide program design.

Partnerships with universities and research institutes can help develop “headlight” data systems that anticipate skill demand. AI itself may become a key tool for analyzing patterns invisible to traditional methods. The National Science Foundation has funded a new project to test approaches for creating labor market information methodologies and tools that are more sensitive to emerging technologies and create greater insight into worker skills and learning histories.[17]

Partnerships with universities and research institutes can help develop “headlight” data systems that anticipate skill demand.

Conclusion: A Narrowing Window

AI is reshaping the economy in real time, eliminating the entry-level roles that once served as training grounds and raising the premium on hybrid human-AI skills. For state education boards, the task is urgent but achievable:

- Redesign curricula and graduation requirements for AI fluency.

- Expand access to tools, mentors, and credentials especially for disadvantaged and rural populations.

- Build pathways that emphasize lifelong learning and human-centered skills.

- Partner with employers to align education with demand.

The window for preparation is narrowing. Boards that act decisively now can give their students a head start in the AI economy. While it will be necessary to be cautious and open minded to the swift economic and social changes that will occur due to AI, it is clear that those that delay risk leaving a generation unprepared for the life and career realities they will face.

Brent Orrell is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.

Notes

[1] These attributes go by several names, including noncognitive, soft, and durable skills.

[2] US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment by Major Industry Sector, table 2.1.

[3] Brent Orrell, “De-Skilling the Knowledge Economy,” brief (Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute, June 25, 2025).

[4] Matthew Urwin, “Is Your Job AI-Proof? What to Know About AI Taking Over Jobs,” Built In, August 27, 2025, https://www.builtin/artificial-intelligence/ai-replacing-jobs-creating-jobs.

[5] Kevin Bahr, “U.S. Manufacturing Employment: A Long-Term Perspective,” CPS Blog, January 29, 2025.

[6] David J. Deming and Mikko I. Silliman, “Skills and Human Capital in the Labor Market,” Working Paper No. 32908 (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, September 2024).

[7] David J. Deming, “The Growing Importance of Social Skills in the Labor Market,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 132, no. 4 (2017): 1593–640, https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjx022.

[8] Gergely Orosz, “State of the Software Engineering Job Market in 2024,” The Pragmatic Engineer newsletter, October 22, 2024.

[9] Erik Brynjolfsson, Bharat Chandar, and Ruyu Chen, “Canaries in the Coal Mine? Six Facts about the Recent Employment Effects of Artificial Intelligence,” working paper (Stanford, CA: Stanford Digital Economy Lab, August 26, 2025) ; Enrique Ide, “Automation, AI, and the Intergenerational Transfer of Knowledge,” IESE Business School Working Paper (Barcelona: IESE Business School, July 22, 2025), https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5360803.

[10] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, “AI and the Future of Skills, Volume 2: Capabilities and Assessments,” report (Paris: OECD, November 18, 2021), https://doi.org/10.1787/a9fe53cb-en; US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Occupational Outlook Handbook, website; David Autor, David A. Mindell, and Elisabeth B. Reynolds, The Work of the Future: Building Better Jobs in an Age of Intelligent Machines (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2022); Deming, “The Growing Importance of Social Skills”; Molly Kinder et al., “Generative AI, the American Worker, and the Future of Work,” research (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, October 10, 2024); Michael Chui et al., “The Economic Potential of Generative AI: The Next Productivity Frontier,” report (McKinsey & Company, June 14, 2023); World Economic Forum, Future of Jobs Report 2023 (Geneva: WEF, May 2023).

[11] Brent Orrell, “STEM without Fruit: How Noncognitive Skills Improve Workforce Outcomes,” brief (Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute, November 14, 2018).

[12] NVIDIA, “Utah to Advance AI Education, Training,” post, March 10, 2025.

[13] American Welding Society, “Shining a Light on the Welding Workforce,” web page (2025); US Bureau of Labor Statistics, ”Occupational Outlook Handbook: Electricians,” August 28, 2025.

[14] North Dakota Career and Technical Education, “Apprenticeship,” web page.

[15] Stanford Center on Longevity, “Education and Learning for Longer Lives: Designing the Future,” web page.

[16] Health Resources and Services Administration, “Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program,” web page; Friends of the Children, website.

[17] Brent Orrell, Suzette Kent, and Jason Owen-Smith, “AI Will Have a Major Impact on Labor Markets. Here’s How the US Can Prepare,” FedScoop op-ed, December 31, 2024.

Also In this Issue

The Role of State Boards in Making Credentials’ Value Transparent

By Scott CheneyNot all credentials are created equal, so how will students and families choose?

Weighing the Value of Industry-Based Certifications against Their Costs

By Madison E. Andrews, Kaitlin Ogden and Matt S. GianiA study of Texas’s move to offer bonuses and add accountability measures for attainment reveals some unintended consequences.

Remaking Transcripts to Better Reflect Students’ Competencies

By Celina Pierrottet and Jon AlfuthState boards wanting to capture student mastery in new ways have many considerations to take into account.

Turning Graduate Portraits into Pathways

By Laura SloverNorth Carolina and Indiana are leading in the push toward teaching and assessing durable skills.

Deskilling the Knowledge Economy: Implications for Schools

By Brent OrrellTo foster students’ entry into the workforce, their schools will need to equip them with AI-complementary skills.

i

i

i

i

i

i