What Role Do States Play in Selecting K-12 Textbooks?

A network of states move the needle on quality without usurping local control.

High-quality K-12 instructional materials can meaningfully improve teaching practice and student achievement, especially when paired with professional learning support.[1] Yet state policymakers have usually left ultimate authority for textbook selection to school district leaders.[2] Consequently, the quality of materials across U.S. classrooms and within states varies, with potentially detrimental effects on student learning.

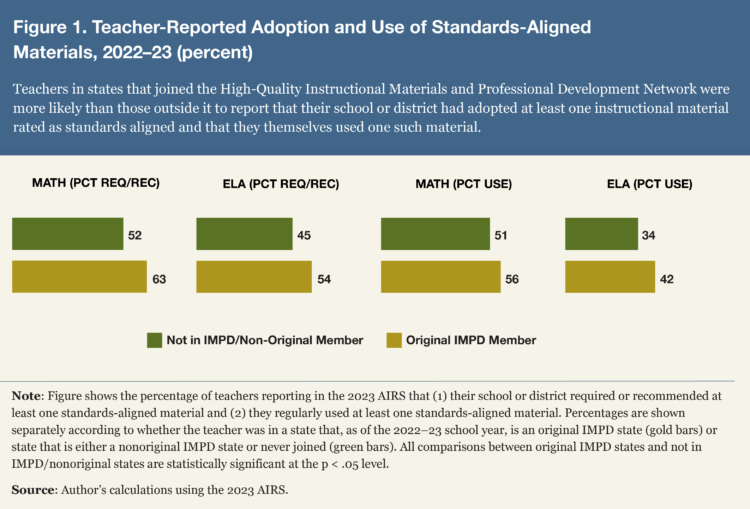

Yet a growing number of states have been creatively mixing policy, guidance, and supports to promote the use of high-quality instructional materials (HQIM) at the local level. Our own RAND American Teacher Panel survey data suggest that these strategies are working: Adoption of high-quality English language arts and mathematics instructional materials is higher among K-12 schools in those states, as are teachers’ reports that they use those materials regularly in their instruction.

What Do Textbook Policies Look Like?

State textbook adoption policies can be broadly divided into two categories: state adoption states and local adoption states.[3] In the 19 states with state policies, state-appointed boards are responsible for reviewing textbooks and creating lists of “adopted” or “approved” textbooks for districts to consider. In the remaining states, districts are largely left to shift for themselves based on their own criteria.[4]

Policy across the 19 state adoption states varies greatly. For example, in Tennessee, Rhode Island, and Nevada, districts must adopt state-approved textbooks or seek a waiver to use a nonapproved textbook. But in Texas and New Mexico, adoption lists are recommendations, not mandates.

Even when districts adopt a textbook from a state-approved list, our research indicates that only a third of teachers use that textbook regularly with little or no modification.[5] More commonly, teachers heavily modify the textbooks they are provided, assembling lesson plans that draw from multiple textbooks or relying on lesson plans that they have created entirely by themselves. For states looking to increase the amount of actual classroom instruction driven by high-quality materials, influencing local adoption is only the first step.

Creating Conditions for HQIM Use

Louisiana was one of the first states to take a more assertive role to not only inform district textbook adoption but also pair adoptions with high-quality supports for teachers.[6] Beginning roughly in 2012, the Louisiana Department of Education began focusing on curriculum materials as central to the delivery of standards-aligned instruction. The department began to publish reviews of commonly used K-12 textbooks for math and English, with clear information about what was high quality and standards aligned and what was not. The department also made it easier for districts to adopt curriculum materials that reviewers hired under state contracts deemed as high quality. Staff also identified professional development vendors that explicitly focus on supporting implementation of designated high-quality materials, and they made sure that state and benchmark assessment tools were aligned with those materials.

Drawing heavily upon the example of Louisiana, the Council of Chief State School Officers formed the High-Quality Instructional Materials and Professional Development (IMPD) Network in 2017. The network develops and shares strategies to increase adoption and use of HQIM. We have been studying those strategies since it formed. We group them into three categories: mandates, signals, and incentives.

Mandates. Certain states with state adoption policies enforce the use of state-selected instructional materials. While universal textbook mandates are rare, several states have recently mandated the adoption of approved materials in select grades and subjects—namely, reading instruction. As of 2022, 12 states required districts to choose state-approved reading materials. In several of these states, including Kentucky, Arkansas, and Delaware, mandates are restricted to reading materials for early elementary grades and were spurred by recent legislation intended to promote the science of reading in classrooms.[7]

As of 2022, 12 states required districts to choose state-approved reading materials.

Signals. Absent mandates, many states opt to signal districts on what constitutes high-quality materials. District processes for selecting textbooks can be complex and redundant to processes conducted at the state level or to other districts within the state.[8] State adoption lists are a straightforward mechanism for signaling quality. By doing so, states can save districts’ time and money while also seeding local selection processes with several high-quality options.

Incentives. Or states can use incentives to get districts to adopt state-recommended materials. Many states offer districts grants to adopt high-quality materials and provide professional development aligned specifically to those materials. One example is the Delaware Reimagining Professional Learning program, which annually provides grants to Delaware districts to fund professional learning. Eligibility is contingent on teachers having access to high-quality materials, as the state defines it. States can also make procuring recommended materials easier for districts. For example, Oregon, Massachusetts, and Idaho have master contracts for adopted materials, allowing districts to circumvent individual negotiations with publishers for textbooks and other materials.

States should keep in mind that no mandate, signal, or incentive can ensure that teachers, schools, and districts will buy into the importance of high-quality materials or recommendations or requirements regarding what quality is. In fact, certain states such as Wyoming explicitly prohibit state boards from listing approved materials, emphasizing that material selection is strictly a local decision.

No mandate, signal, or incentive can ensure that teachers, schools, and districts will buy into the importance of high-quality materials or recommendations or requirements regarding what quality is.

States must walk a tightrope of guiding schools and districts toward choosing and using high-quality materials while maintaining local agency and trust. A straightforward way to maintain local autonomy is to provide many HQIM options for districts to choose from rather than prescribing a specific material.[9]

Some states have addressed this tension by partnering with national organizations dedicated to promoting HQIM use and awareness. Some states partner with EdReports, an independent organization whose national teams of educators regularly review comprehensive curriculum materials. By working with EdReports, states have been able to address a common challenge of keeping adoption lists up to date with newly released materials. Because EdReports reviews materials on a rolling basis, states can integrate EdReports ratings with their own, allowing them to release information on new materials on a more timely basis and encourage adoption of the newest releases that might otherwise go underused.

Many states use EdReports ratings as a foundation for their state-specific material ratings or recommendations. Many state platforms for material ratings, such as Ohio Materials Matters and the Arkansas Initiative for Instructional Materials, integrate EdReports ratings directly. Other states, such as Massachusetts and Mississippi, use state-specific rating systems but either directly consulted with EdReports to inform the development of these systems or point to EdReports as an additional resource for material ratings.

Another way states can address buy-in challenges is to partner with experienced educators. For example, Ohio and Mississippi are developing cohorts of active educators who serve as “curriculum ambassadors” for the states’ instructional material initiatives. Ambassadors are touchpoints within their schools and districts for questions about selecting, using, and supporting HQIM and help states build expertise and trust through teacher networks.

Is It Working?

Our research has captured, in real time, how curriculum efforts may be shaping what teachers do in the classroom. According to the RAND American Instructional Resources Surveys of teachers and principals, teachers in states that are a part of CCSSO’s IMPD network were more likely to report access to and supports for HQIM.[10] Beginning with the 2018–19 school year, the surveys have been fielded annually to a nationally representative sample of over 8,000 K-12 teachers, as well as state representative samples in all the network states. We used EdReports ratings to rate whether the materials teachers reported their district adopting and themselves using in each year were aligned to state standards.

During the 2022–23 school year, teachers within IMPD states that joined the network as part of its initial cohort in 2017[11] were both significantly more likely to report that their school or district had adopted at least one instructional material that EdReports rated as standards aligned and that they themselves used one such material (figure 1).

Importantly, the IMPD cohort have not embraced a uniform set of HQIM initiatives and policies. Rhode Island holds the most authority when it comes to instructional materials: It has required all its local education agencies (LEAs) to adopt state-approved high-quality curricula in math and ELA by 2023. By comparison, Mississippi and New Mexico formally adopt textbooks at the state level but do not require LEAs to adopt them. And while Delaware, Massachusetts, and Nebraska do not officially adopt materials, they publish state-specific reviews to help LEAs make wise textbook decisions.

Given the emphasis on local control in textbook processes and the varied policy landscape across the country, it is a promising sign that rates of adoption and use of standards-aligned textbooks are significantly higher among states that have participated in the IMPD network the longest. It shows that state efforts can change teacher, school, and district behaviors.

Lessons from Our Research

For states hoping to start or further their instructional material initiatives, our research suggests several key considerations. First, states have the authority and opportunity to make a difference in the materials that are adopted and used in K-12 public school classrooms. State leaders may not grasp all the ways they can exercise that authority, but if they explore options and seek advice from leading states, they could ensure that a bigger proportion of teachers and classrooms are using curriculum materials that align closely to their state academic standards.

Second, state and district requirements for use of high-quality materials, regardless of the strategy for doing so, is just a first step—albeit an important step—in ensuring their use. Our data shows that teachers in IMPD states and in districts that have adopted standards-aligned materials are much more likely to report curriculum-aligned supports like professional development and coaching that address their required curriculum. When it comes to promoting HQIM, a strategy of “making the right choice the easy choice” appears successful. To carry this out, states will have to think carefully about the supports that teachers, schools, and districts will need after purchasing decisions are made.

States will have to think carefully about the supports that teachers, schools, and districts will need after purchasing decisions are made.

Third, the success of these initiatives will be contingent on gaining buy-in from district and school leaders. Traditionally, curriculum material adoption in K-12 public schools has been a local decision. Thus, local leaders need to be brought into conversations about materials adoption. But once engaged, they can play a major role in fostering use of standards-aligned materials. According to our data, teachers reporting that their principals encourage them to use required curricula or incorporate curricula into teacher observation processes are more likely to use these materials for the majority of their instructional time. Building local leaders’ knowledge about high-quality materials not only builds buy-in for decisions on what to purchase, it also turns leaders into resources to aid implementation.

Sy Doan is a policy researcher and Julia Kaufman is associate research department director for the Behavioral and Policy Sciences Department and a senior policy researcher at the RAND Corporation.

Notes

[1] Matthew Chingos and Grover Whitehurst, “Blindly: Instructional Materials, Teacher Effectiveness, and the Common Core” (Washington, DC: Brookings, April 2012); Thomas Kane et al., “Teaching Higher: Education’s Perspectives on Common Core Implementation” (Cambridge, MA: Center for Education Policy Research, Harvard University, February 2016); Heather Hill et al., “Professional Development That Improves STEM Outcomes,” Phi Delta Kappan 101, no. 5 (2020).

[2] Michael Watt, “Research on the Textbook Selection Process in the United States of America,” IARTEM e-Journal 2, no. 1 (2009).

[3] Erin Whinnery, Lauren Bloomquist, and Gerardo Silva-Padron, “Your Question: You Asked for Information on Textbook Adoption Policies,” Response to Information Request (Education Commission of the States, 2022).

[4] Emily Schmidt, “Required Reading: How Textbook Adoption in Three States Influences the Nation’s K-12 Population,” American Public Media, June 2, 2022.

[5] Julia H. Kaufman et al., “How Instructional Materials Are Used and Supported in U.S. K-12 Classrooms: Findings from the American Instructional Resources Survey” (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2020).

[6] Julia H. Kaufman et al., “Creating a Coherent System to Support Instruction Aligned with State Standards: Promising Practices of the Louisiana Department of Education” (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2016); Julia H. Kaufman et al., “Raising the Bar: Louisiana’s Strategies for Improving Student Outcomes” (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018); Julia H. Kaufman et al., “Raising the Bar for K–12 Academics: Early Signals on How Louisiana’s Education Policy Strategies Are Working for Schools, Teachers, and Students“ (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2019).

[7] Christopher Peak, “How Legislation on Reading Instruction Is Changing across the Country,” American Public Media, November 17, 2022.

[8] Morgan Polikoff, “The Challenges of Curriculum Materials as a Reform Lever,” Evidence Speaks Reports 2, no. 58 (Washington, DC: Brookings, June 28, 2018).

[9] Morgan Polikoff, Beyond Standards: The Fragmentation of Education Governance and the Promise of Curriculum Reform (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press, 2023).

[10] Sy Doan, et al., “How States Are Creating Conditions for Use of High-Quality Instructional Materials in K-12 Classrooms: Findings from the 2021 American Instructional Resources Survey” (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2022).

[11] Delaware, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Nebraska, New Mexico, and Rhode Island.

Also In this Issue

What Role Do States Play in Selecting K-12 Textbooks?

By Sy Doan and Julia KaufmanA network of states move the needle on quality without usurping local control.

States Take Many Paths to Advance High-Quality Curriculum and Align Professional Learning

By Jocelyn Pickford and Kate PoteetState boards can take a lesson from the work of leading states.

The Unrealized Promise of High-Quality Instructional Materials

By David SteinerOvercoming barriers to faithful implementation requires changing teacher and leader mind-sets.

The State of K-12 Science Curriculum

By Sam Shaw and Eric HirschWhile the availability of aligned, high-quality materials lags what science standards demand, states can press the market for better ones.

How Background Knowledge Builds Good Readers and Why Knowledge Building ELA Curricula Are Vital

By Ruth WattenbergA common base of content knowledge and coherent, comprehensive, and sequential curricula to deliver it are prerequisites for reading comprehension. Most students are not getting what they need.

i

i

i

i