The Unrealized Promise of High-Quality Instructional Materials

Overcoming barriers to faithful implementation requires changing teacher and leader mind-sets.

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” —Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities

In the richly heterogeneous United States, teachers largely decide what students learn. Even in states where state boards adopt a long list of instructional materials, districts can get waivers to substitute their own choices.[1] And even when districts do pick materials, teachers do not necessarily teach them in toto.

Almost 90 percent of America’s public school teachers add, mix, and match a plethora of content from the internet into their district-mandated content, with Teachers Pay Teachers the most consulted source, according to RAND.[2] One survey found that teachers spend, on average, seven hours per week searching for materials, and an additional five hours per week creating their own content.[3]

This work of curriculum construction largely takes place privately and without supervision. As the RAND report points out, “There is little research on the standards alignment, quality, and effectiveness of digital [online] materials. As a result, teachers might rely on trial and error or anecdotal advice from peers instead of rigorous evidence and research when selecting digital materials.”[4]

The problem is not simply that teachers are pulling materials of uncertain quality from the internet. Rather, the more serious concern is that this behavior ensures that the material a child studies in school differs from classroom to classroom. Thus, the caliber, rigor, and any rational sequencing of that material both within and across grade levels becomes a matter of luck and chance.

The caliber, rigor, and any rational sequencing of material both within and across grade levels becomes a matter of luck and chance.

Nor are teachers prepared for this role: No school of education in the United States offers courses on how to successfully meld an assortment of digital resources with a district-mandated curriculum. More troubling, much of the material teachers select by themselves is below grade level. According to survey research by the nonprofit TNTP, “Students spent more than 500 hours per school year on assignments that weren’t appropriate for their grade and with instruction that didn’t ask enough of them—the equivalent of six months of wasted class time in each core subject.”[5]

Still more concerning is the striking disparity between classrooms of wealthy and of low-income students: “Classrooms that served predominantly students from higher income backgrounds spent twice as much time on grade-appropriate assignments and five times as much time with strong instruction, compared to classrooms with predominantly students from low-income backgrounds.”[6]

Do Better Curricula Make a Difference?

Evidence from overseas strongly supports the general conclusion that top-performing nations each have rigorous curricula, often issued at the national or province (what we would call state) level:

Despite the vast cultural, demographic, political, and geographic diversity of Finland, Hong Kong, South Korea, Canada, Japan, New Zealand, Australia, the Netherlands, and Switzerland, their educational systems all emphasized content-rich curriculum and commensurate standards and assessments.[7]

Over the last decade, U.S. researchers have also linked high-quality instructional materials (HQIM) and positive student learning outcomes. Most recently, David Grissmer and colleagues studied the impact of the use of the Core Knowledge Sequence, a curriculum approach to explicitly build background knowledge.[8] On average, students in schools that used the curriculum scored a statistically significant 16 percentage points higher on end-of-year state tests than a control group of students who did not, after controlling for race, gender, and free and reduced-price lunch eligibility.

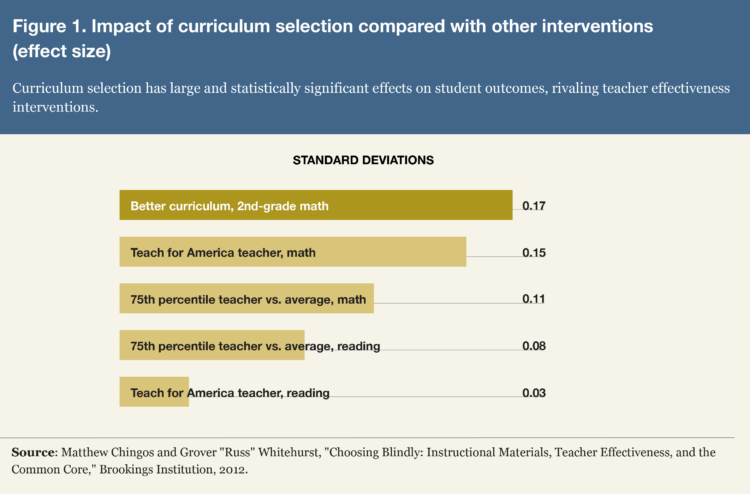

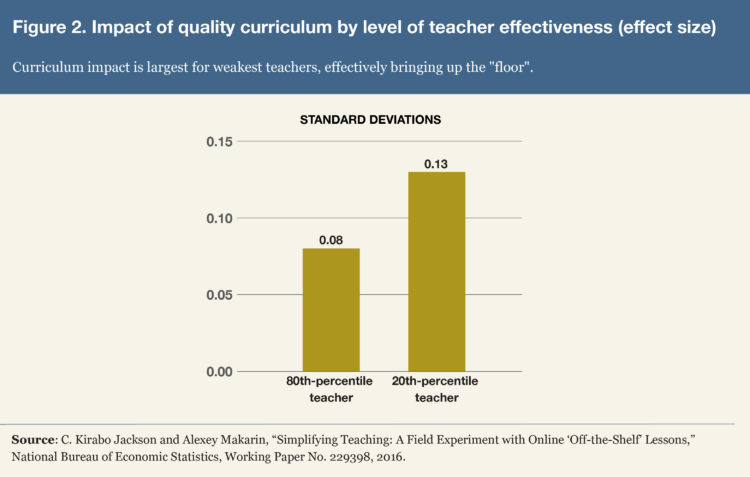

Grissmer’s research builds on earlier findings. Several studies find that the choice of math and science textbooks had significant effects on test scores, and other studies indicate a positive impact in English language arts (ELA) based on better textbooks.[9] One study favorably compares the impact of better curriculum with that of other interventions (figure 1), and another suggests that the greatest positive impact of HQIM accrues when used by the least experienced teachers (figure 2).

There has been no shortage of success stories at the individual district level. For example, one year after implementing a new HQIM math curriculum, Duval County public schools in Florida reported “extraordinary improvement” in grade 3, 4, and 5 math in 2016.[10] Duval superintendent Nikolai Vitti said the county saw a six percentage point improvement in grade 3 compared with a statewide improvement of three percentage points. In grade 4, scores improved by three percentage points, whereas the state showed no growth.

Delaware’s Seaford district, whose multilingual student population has doubled over the past decade, went from being one of the state’s lowest-performing districts on state tests to one of its highest after adopting high-quality ELA curriculum.[11]

State Support for HQIM Use

The last few years have seen major progress in the number of U.S. public school districts procuring HQIM in math, ELA, or both on behalf of their teachers and students. Under state superintendent John White, Louisiana pointed the way. Building support for HQIM with teachers across the state produced results that would have once been considered inconceivable, especially given that Louisiana does not mandate adoption of particular textbooks. As of 2021, 99 percent of Louisiana middle and high school students have access to HQIM in both ELA and math.[12]

The last few years have seen major progress in the number of U.S. public school districts procuring HQIM in math, ELA, or both.

Building on the work in Louisiana, the Council of Chief State School Officers launched its Instructional Materials and Professional Development (IMPD) network with the express purpose of building support and sharing best practices for states interested in increasing the use of HQIM. Currently comprising 13 states, the network’s recent research reflects across-the-board progress in HQIM adoption rates.[13]

Perhaps most remarkable has been the progress in Tennessee, where results match those in Louisiana: Virtually the entire state has purchased HQIM for ELA, with 98 percent of its total middle school students—and 99 percent of its middle school students of color and from low-income families—having access to high-quality ELA curriculum. The rates are similar for high school students and above 80 percent for all student groups in elementary schools.

The IMPD states are not alone in taking action to support HQIM use. The Oregon Department of Education, for example, released a report that provides a curated list of research on the importance of HQIM.[14] As part of its plan for spending federal recovery funds, Connecticut opted to design a statewide K-8 model curriculum aligned with HQIM.[15]

Changing Mind-Sets

Research from the past decade, as well as prior studies, point in the same direction: Curriculum materials matter.[16] Yet the findings as a whole do not constitute a slam dunk. Perhaps most concerning, David Blazar, Thomas Kane, and colleagues found essentially zero positive impact on student learning from the implementation of a new math curricula across the country during school years 2014–15 through 2016–17.[17]

That same research also provides some reasons why. Simply put, teachers are not using materials they are given with any serious level of fidelity. For example, they might have used an example or two from the new curriculum or some of its exercises for a homework assignment, but for the most part, teachers were bypassing the new curricula. Many of those surveyed swapped out materials but left instruction unchanged, Kane said in a piece he wrote with me:

Many teachers are using the new curricula in cursory ways. Although 93 percent of the 1,195 teachers surveyed reported using the textbook for some purpose in more than half their classes, only 25 percent used it “nearly all the time” for essential activities such as in-class examples, in-class exercises, homework problems, and assessments, and just 7 percent use their curriculum exclusively. Moreover, teachers using the more rigorous curricula (as many as 40 percent in the case of Eureka Math, one of the curricula studied in the report) report watering down the curriculum when they believe it is too demanding for their students.[18]

Clearly, if teachers do not regularly use a curriculum, its impact on student learning outcomes will be unsurprisingly negligible.

Blazar et al. surface a striking reason teachers do not use HQIM: “The average teacher received only 1.1 days of professional development (PD) devoted to their curriculum during the 2016–17 school year and 3.4 days when including prior years.”[19] A day and a breakfast of PD per year is unlikely to change teaching practice in the great majority of cases—especially given that the typical U.S. public school teacher in the United States has been teaching for 14 years.[20]

The link between meager PD and underusage of HQIM is a critical factor—though not the only one. A 2016 study by Kane and colleagues found that the use of new materials was positively correlated with “more professional development days, more classroom observations followed by feedback tied to the Common Core, and the inclusion of Common Core–aligned student outcomes in teacher evaluations.” In other words, while PD matters, so does the school environment—specifically, the degree to which other factors reinforce teachers’ usage of new materials. In this study, those factors were principals’ observations and evaluations.[21]

While PD matters, so does the degree to which other factors reinforce teachers’ usage of new materials.

Similarly, in a study of the efficacy of the Core Knowledge Sequence in 2000, researchers concluded, “Successful implementation relied on instructional leadership from the principal … and support from the district or at least a commitment that the district would enable rather than hinder long-term implementation.”[22]

In short, context matters. Cursory PD coupled with principals who give little more than lip service to HQIM send powerful signals to teachers that the district and school are not serious about implementation. An additional factor is whether teachers perceive that the new curriculum helps or hinders students’ attainment of state learning standards and prepares them adequately for state assessments.

States and districts must make a strong case for HQIM. Changing the mind-set of teachers—especially those with years of experience—requires respecting their expertise and appealing to them through good research. Evidence from Louisiana suggests that four evidence-based arguments are especially effective:

- Quality curriculum has a larger impact on student achievement than many common school improvement interventions and costs less.

- Whole-class exposure to rigorous, content-rich curriculum increases both quality and equity.

- High-quality curriculum supports teachers’ practice and helps them to develop subject expertise.

- Externally developed curriculum materials free teachers up to focus on effective pedagogy—how to teach—instead of spending time developing materials from scratch.[23]

Researchers at my organization, the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy, have identified other potential barriers in specific districts.

- Teachers think their students cannot manage rigorous new curricula. Possible solutions include more extensive PD on the new materials, more support for accelerated learning through the use of just-in-time diagnostics, and the use of these diagnostic tests to support the effective use of targeted, differentiated instruction and high-dosage tutoring.[24]

- Teachers use multiple sources of curriculum material. Possible solutions include sharing research with local schools of education to undermine the prevailing view that only teacher-created curriculum is truly authentic, building curriculum-specific elements into principals’ classroom observation rubrics, and ensuring that district PD discourages teachers from diluting curriculum with ad hoc items from the internet.

- Teachers lack a basic incentive to teach using HQIM for English due to assessment misalignment. Possible solutions include standards-aligned formative assessments to evaluate progress toward overall growth goals, targeted instructional interventions for students, and preparation of students for the rigor of summative assessments.

Conclusion

Instructional materials are the core of education. Their quality matters. However, higher quality and more rigorous materials are challenging to implement in the classroom. While states have found strong, effective levers to incentivize their school districts to adopt HQIM, teachers can still be reluctant to use these materials consistently. Longstanding habits of creating unique curricular content, combined with the perception that most students will not be able to manage the new, more rigorous HQIM content, work against change. So too do district policies that provide only a light dusting of PD to support the use of HQIM.

Perhaps the greatest harm comes through the signals that principals give when they fail to make HQIM a priority in classroom observations and feedback to teachers. State boards of education and the departments of education they oversee have a shared responsibility not simply to support the universal use of HQIM in their districts but to ensure that district superintendents are well versed in the research on how best to work with teachers to make effective implementation a reality in America’s schools.

Dr. David Steiner is executive director of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy.

Notes

[1] Emily Schmidt, “Required Reading: How Textbook Adoption in 3 States Influences the Nation’s K-12 Population,” APM Research Lab blog, June 2, 2022; Chiefs for Change, “Choosing Wisely: How States Can Help Districts Adopt High-Quality Instructional Materials” (Washington, DC: Chiefs for Change, April 2019).

[2] Katie Tosh et al., “Digital Instructional Materials: What Are Teachers Using and What Barriers Exist?” Insights from the American Education Panels (RAND Corporation, 2020).

[3] Nicole Gorman, “Survey Finds Teachers Spend 7 Hours Per Week Searching for Instructional Materials,” Education World, February 7, 2017.

[4] Tosh et al., “Digital Instructional Materials.”

[5] TNTP, “The Opportunity Myth: What Students Can Show Us about How School Is Letting Them Down—and How to Fix It” (New York: TNTP, September 25, 2018).

[6] Ibid., p. 4.

[7] Common Core, “Why We’re Behind: What Top Nations Teach Their Students but We Don’t,” Research Report (2009).

[8] David Grissmer et al., “A Kindergarten Lottery Evaluation of Core Knowledge Charter Schools: Should Building General Knowledge Have a Central Role in Educational and Social Science Research and Policy?” EdWorking Paper 23-755 (Annenberg Institute at Brown University, April 2023).

[9] Cory Koedel and Morgan Polikoff, “Big Bang for Just a Few Bucks: The Impact of Math Textbooks in California,” Evidence Speaks Reports 2, no. 5 (Washington, DC: Brooking, January 5, 2017); Morgan S. Polikoff, “How Well Aligned Are Textbooks to the Common Core Standards in Mathematics?” American Educational Research Journal 52, no. 6 (December 2015): 1185–1211; A.A. Zucker et al., “Learning Science in Grades 3–8 Using Probeware and Computers: Findings from the TEEMSS II Project,” Journal of Science Education and Technology 17, no. 1 (2008): 42–48; Thomas Kane et al., “Teaching Higher: Educators’ Perspectives on Common Core Implementation” (Cambridge, MA: Center for Education Policy Research, Harvard University, February 2016); G.D. Borman, N.M. Dowling, and C. Schneck, “A Multisite Cluster Randomized Field Trial of Open Court Reading,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 30, no. 4 (2008): 389–407.

[10] David Steiner, conversation with Superintendent Nikolai Vitti, October 27, 2016.

[11] Kelly Carvajal Hageman, “Curriculum Case Study: How One School District in the ‘Nylon Capital of the World’ Once Faced State Takeover for Poor Performance, Then Became Among the Best in Delaware,” the 74, May 24, 2021.

[12] CCSSO, “High Quality Instructional Materials & Professional Development Network Case Study: Impact of the CCSSO IMPD Network,” brief (Washington, DC, January 2022), 8.

[13] Julia H. Kaufman, Sy Doan, and Maria-Paz Fernandez, “The Rise of Standards-Aligned Instructional Materials for U.S. K-12 Mathematics and English Language Arts Instruction: Findings from the 2021 American Instructional Resources Survey,” Data Note (RAND, 2021).

[14] Oregon Department of Education, “Importance of High-Quality Instructional Materials” (Spring 2023).

[15] “Connecticut to Develop Model Curricula, Invest in Teacher-Led Implementation,” Education Recovery Hub website (Collaborative for Student Success, January 19, 2022).

[16] David Steiner, “Curriculum Research: What We Know and Where We Need to Go,” research, StandardsWork (March 2017).

[17] David Blazar et al., “Learning by the Book,” research report (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, March 2019).

[18] David M. Steiner and Thomas J. Kane, “Don’t Give Up on Curriculum Reform Just Yet,” Education Week 38, no. 28 (April 1, 2019): 26–27.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Tim Walker, “Who Is the Average U.S. Teacher?” NEA News, June 8, 2018.

[21] Kane et al., “Teaching Higher.”

[22] Sam Stringfield et al., “National Evaluation of Core Knowledge Sequence Implementation: Final Report” (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Center for Research on the Education of Students Placed at Risk, 2020).

[23] Jacqueline Magee and Ben Jensen, “Overcoming Challenges Facing Contemporary Curriculum” (Melbourne, Australia: Learning First, November 2018).

[24] Simaran Bakshi and David Steiner, “Acceleration, Not Remediation: Lessons from the Field,” Flypaper blog (Thomas B. Fordham Institute, June 26, 2020).

Also In this Issue

What Role Do States Play in Selecting K-12 Textbooks?

By Sy Doan and Julia KaufmanA network of states move the needle on quality without usurping local control.

States Take Many Paths to Advance High-Quality Curriculum and Align Professional Learning

By Jocelyn Pickford and Kate PoteetState boards can take a lesson from the work of leading states.

The Unrealized Promise of High-Quality Instructional Materials

By David SteinerOvercoming barriers to faithful implementation requires changing teacher and leader mind-sets.

The State of K-12 Science Curriculum

By Sam Shaw and Eric HirschWhile the availability of aligned, high-quality materials lags what science standards demand, states can press the market for better ones.

How Background Knowledge Builds Good Readers and Why Knowledge Building ELA Curricula Are Vital

By Ruth WattenbergA common base of content knowledge and coherent, comprehensive, and sequential curricula to deliver it are prerequisites for reading comprehension. Most students are not getting what they need.

i

i

i

i

i

i