Getting Postsecondary Outcomes Data to K-12 Leaders

After the class of 2026 crosses the high school graduation stage this spring, many district and school leaders and counselors will have little idea what happens to those students next. Nor are they equipped to track what is going on with the class of 2025 or those who came before. In too many states, the education system is not set up to give leaders and staff the information they need to ensure they are preparing students for their next steps. State boards of education can fix this.

In too many states, the education system is not set up to give leaders and staff the information they need to ensure they are preparing students for their next steps.

Most states already contract with the National Student Clearinghouse (NSC), a nonprofit that collects enrollment, persistence, and completion data from over 97 percent of US postsecondary institutions. This data is indispensable for understanding whether students are enrolling in a postsecondary institution, where they go, whether they stay enrolled, and whether they complete a credential or degree.

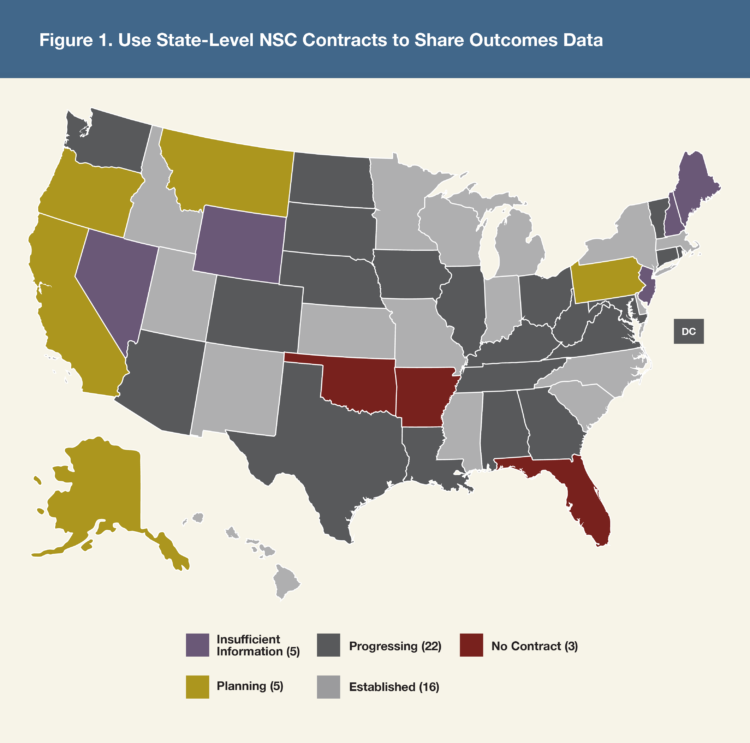

My organization, the National College Attainment Network, estimates that only 22 states currently share postsecondary outcomes data in a meaningful way with their local education agencies (LEAs) (figure 1).[1] Even fewer provide student-level access. Consequently, the high school counselors and administrators charged with ensuring students’ postsecondary success are too often flying blind. They lack the data about previous class outcomes that ought to inform present and future classes’ pathways. Such data could help them evaluate program effectiveness, analyze gaps, and tailor student supports.

Some states are already leading on providing districts this data—and the wherewithal to act upon it:

- North Carolina offers custom reports to districts and technical assistance on how to interpret them.[2]

- Michigan’s MI School Data portal combines NSC data with in-state information to create accessible reports.[3]

- Minnesota supports regional coaching networks to build district capacity to interpret and act on the data.[4]

State boards should ensure their agencies are regularly and securely sending districts postsecondary outcomes data from the NSC or from other in-state sources. State agencies should not be waiting for districts to ask or letting them fend for themselves. In addition, state boards can do the following:

- Set expectations for data sharing and transparency in statewide longitudinal data systems. If districts and schools cannot readily say where their graduates went and how they did when they got there, state boards should ask why.

- Review contracts between state agencies and the NSC to ensure their provisions allow for sharing with LEAs, and ensure that the state agencies have a process for doing so that balances efficiency with data privacy and protections.

- Support technical assistance (e.g., training courses, webinars, a help desk) so districts can interpret and act on the data.

K-12 access to postsecondary outcomes data is essential to improving college and career readiness outcomes and measuring long-term success. This data can shine a light on the steps of past graduates and make the way clearer for graduates to come.

Bill DeBaun is a senior director at the National College Attainment Network (NCAN) in Washington, DC. He can be reached at debaunb@ncan.org.

Notes

[1] Bill DeBaun, “How States Are (and Aren’t) Sharing Postsecondary Outcomes Data with K-12: A Snapshot from the Field,” blog (National College Attainment Network, October 23, 2025).

[2] QI Partners, “North Carolina’s Targeted Support for Districts: Supporting the Use of Postsecondary Outcomes Data,” case study (N.d.).

[3] QI Partners, “Michigan’s Use of Postsecondary Outcomes Data: MI School Data Portal,” case study (N.d.).

[4] QI Partners, “Minnesota’s Regional Coaching Network: Supporting the Use of Postsecondary Outcomes Data,” case study (N.d.).

Also In this Issue

The Role of State Boards in Making Credentials’ Value Transparent

By Scott CheneyNot all credentials are created equal, so how will students and families choose?

Weighing the Value of Industry-Based Certifications against Their Costs

By Madison E. Andrews, Kaitlin Ogden and Matt S. GianiA study of Texas’s move to offer bonuses and add accountability measures for attainment reveals some unintended consequences.

Remaking Transcripts to Better Reflect Students’ Competencies

By Celina Pierrottet and Jon AlfuthState boards wanting to capture student mastery in new ways have many considerations to take into account.

Turning Graduate Portraits into Pathways

By Laura SloverNorth Carolina and Indiana are leading in the push toward teaching and assessing durable skills.

Deskilling the Knowledge Economy: Implications for Schools

By Brent OrrellTo foster students’ entry into the workforce, their schools will need to equip them with AI-complementary skills.

i

i

i

i

i

i