FAFSA as a Pathway to Postsecondary Education

Learning from early adopters of universal FAFSA can help other states design and implement effective policies.

Each year, millions of students access financial aid to attend postsecondary programs by completing the Free Application for Federal Financial Aid (FAFSA).[1] Completing a FAFSA determines students’ eligibility for Pell grants, federal work-study, and federal loans and thus smooths more students’ paths to attaining bachelor’s and associate degree programs, as well as career and technical programs. Cost is one of the most important factors for people deciding to pursue a postsecondary degree.[2] Learning about financial aid eligibility by completing the FAFSA is oftentimes the reason a student chooses to enroll in college or not.

Yet many who are eligible for financial aid do not complete it. Over 1.6 million graduates from the high school class of 2023 did not fill out the FAFSA, leaving over $4 billion in Pell grants on the table.[3]

There are many reasons students do not fill out a FAFSA. Some are misinformed, believing they or their family are not eligible for financial aid. Many are wary of taking on debt, believing that FAFSA is just about qualifying for loans. Others do not get help in how to complete the form.[4] Last year, students encountered difficulties when trying to complete the form due to the three-month delayed rollout of the FAFSA. Even if students accessed studentaid.gov, which had both announced and unannounced web page closures, many experienced technical bugs and glitches that prevented them from submitting the form.

Institutions also saw a collective 5.1 percent enrollment decline for the years 2019 and 2020 during COVID-19.[5] Many students graduated high school feeling unprepared for college after a year of online learning and opted to take a gap year or join the workforce instead. When students do not enroll in college or other postsecondary education programs, they are likely not to complete the FAFSA.

The average tuition, fees, housing, and food price of a bachelor’s degree program increased by 180 percent between 1980 and the 2019–20 school year, and the cost of college continues to be the number one concern for students and families considering attending college.[6] Cost is particularly concerning for first-generation students, students from low-income backgrounds, and students of color who have been historically excluded from college and continue to face numerous barriers when navigating the college-going process. For many students and these students especially, the FAFSA can open doors to many opportunities that will lead them to higher lifetime earnings.

The cost of college continues to be the number one concern for students and families considering attending college.

States Adopt Universal FAFSA

States and communities have taken many steps to increase FAFSA completion rates. Some improved data sharing systems, instituted generous state financial aid and free college programs that make FAFSA completion a prerequisite, and held friendly completion competitions among schools and districts. But some states went further, mandating that every high school senior complete a FAFSA before graduation.

The Louisiana Board of Elementary and Secondary Education approved such a mandate in 2015 for implementation in the 2017–18 school year.[7] Since then, 13 states have passed similar legislation, often on a bipartisan basis, and legislation was introduced but not passed in others.[8]

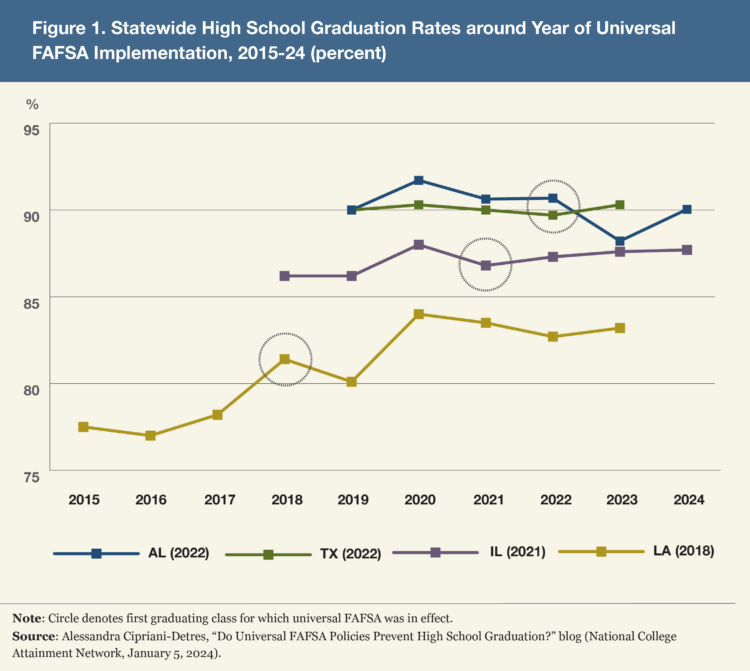

One concern about universal FAFSA policies is that it will prevent students from graduating high school if they choose not to complete the form or cannot complete it due to their immigration status (only US citizens and eligible noncitizens can receive federal financial aid). However, every universal FAFSA policy that has been implemented to date lets students opt out either through a standard form, an alternative application for state financial aid, or both. And universal FAFSA policies generally appear to have no influence on high school graduation rates (figure 1).[9]

Effects of Universal FAFSA

The early adopters—Louisiana, Texas, Alabama, and Illinois—saw increases in FAFSA completion rates for their states’ high school seniors in the year the policy went into effect. Any state that implements a universal policy will see a year-over-year increase in completion rates, but the impact has been especially striking in states that have historically had completion rates lower than the national average. For example, when its universal FAFSA policy went into effect for the class of 2022, Alabama saw a 12 percent increase in the number of seniors who completed a FAFSA over the previous class. Alabama ranked ninth in the country for its high school senior completion rate in 2022, a remarkable jump from being number 34 the year before (figure 2).[10]

When the class of 2021 graduated after an entirely virtual school year during COVID, counselors had to find innovative ways to encourage students to complete their FAFSAs, especially in the states with universal FAFSA policies. National FAFSA completion rates for the class of 2021, the first graduating class to complete a full academic year during the pandemic, decreased by nearly 5 percent compared with the class of 2020.[11] However, Illinois bucked the trend, seeing about a 3 percent increase in completions compared with the year before, when universal FAFSA was not in place.[12] It was the only state to see an increase in 2021.

Policy Design Options

Legislators and other state leaders often grapple with several questions when they mull universal FAFSA laws: Should they mandate FAFSA completion? How can flexibility and the need to accommodate students and families’ unique circumstances be incorporated in such a mandate? Who will implement and support an added graduation requirement?

States have taken different approaches. The most common are making FAFSA completion a statewide high school graduation requirement and delegating implementation to local education agencies (LEAs).

While Louisiana’s universal FAFSA policy was repealed for the 2023–24 school year, support was provided by the Louisiana Office of Student Financial Aid, a state agency that had primarily focused on college access for students. California delegates the responsibility for ensuring FAFSA completion, administration of a state aid application form, and creation of an opt-out process to LEAs and charter schools. While LEAs and charter schools must confirm to state officials that all students have completed a form before graduation, it is not a graduation requirement.

Even when state policies are broadly similar, there are often nuances and innovations that distinguish one universal FAFSA policy from another (table 1).

New Hampshire and Louisiana have repealed their universal FAFSA policy. While the policy led to a significant increase in FAFSA completion rates, state officials in Louisiana cited concerns over financial privacy for families and the unanticipated burden that a FAFSA policy can place on school administrators, school counselors, and families to ensure compliance. During the March 2024 meeting of the Louisiana State Board of Elementary and Secondary Education, board member Conrad Appel expressed concerns that some parents feel “… overwhelmed by the technical details.” Other board members acknowledged the need for continued FAFSA awareness and proposed developing written guidance for school administrators and counselors to support families in completing the application.

Implementation Timeline. The time between a bill’s passage and implementation can vary. While it is recommended that states wait a full calendar year from bill passage to implementation, states such as Alabama waited less than a year.[13] This expedited timeline is often made possible by strong implementation support from state agencies.[14]

Opt-Out Eligibility. A standardized opt-out or waiver process is a key component of a universal FAFSA policy. Opting out of the requirement is especially important for students who are unable to complete the form due to a lack of parental financial information, an immigration status that makes them ineligible, or other extenuating circumstances. All states let either the student or their parent/guardian opt out. Texas, Indiana, and Nebraska delegate opt-out authority to school officials and district personnel in special circumstances. State agencies or individual LEAs and charter schools typically create the forms.

A standardized opt-out or waiver process is a key component of a universal FAFSA policy.

Data Reporting and Accountability. Many states vary in their approaches to FAFSA data reporting and accountability. Five states formally designate a district or school representative to track FAFSA completion and report overall compliance to the state. States that do not have a formal state directive for reporting and accountability typically partner with other state and local agencies to participate in cross-district data sharing.

Considerations for Undocumented Students and Families. Directly or indirectly, policies typically consider students and families who are undocumented. In addition to a standard opt-out waiver, California and Texas have created an application for residents and nonresidents who are ineligible to apply for federal student aid due to their immigration status. Through the California Dream Act Application and Texas Application for State Financial Aid, students still receive in-school support to complete their applications.[15] But indirectly, states rely on the opt-out form as a way to support students, especially if the state has mandated FAFSA completion as a graduation requirement.

Effective Implementation

States with universal FAFSA have lessons on what is important for successful implementation. Schools gain capacity, through increases in staff or partnerships with college access organizations. They also benefit from having data at hand to facilitate targeting students who have not yet completed the FAFSA. These tactics help create a culture conducive to FAFSA completion. Additionally, cross-sector coordination is helpful for planning and sharing resources. California, Louisiana, Texas, and Alabama have included these elements, which have contributed to increases in financial aid applications.

Capacity. Building partnerships, training counselors on financial aid, and securing funding for workshops and financial aid programming are critical steps for districts to take. Local colleges or universities, community-based nonprofits, or the state education agency can all make good partners in this work. In Texas, 20 regional service centers function as intermediaries between their districts and charter schools and the Texas Education Agency. Education Service Center Region 19 helps El Paso, Texas, LEAs with financial aid form completion support and training. The El Paso Community College, the University of Texas at El Paso, Texas Tech, and volunteers from the Texas Workforce Commission help LEAs host events on financial aid form completion.

Building partnerships, training counselors on financial aid, and securing funding for workshops and financial aid programming are critical steps for districts to take.

Data. School counseling staff and nonprofit partners need to know which students have started or completed the FAFSA, and data sharing agreements help. While mandates vary, most states have entered into agreements with the US Department of Education Office of Federal Student Aid to access student-level data on FAFSA submissions and completions.[16] Districts that are effective in finding students who might need support are sharing student FAFSA and state financial aid application progress at least weekly with counselors, teachers, nonprofit organizations, and college access programs.[17] For example, California districts and schools can request student-level data with an accessible agreement as part of the California Student Aid Commission’s Race to Submit initiative.

Cross-State Coordination. Statewide collaboration eases the development and sharing of best practices. For example, Alabama Possible runs the Alabama Goes to College Program, which runs a FAFSA completion campaign for schools and provides resources to students and families about postsecondary options and financial aid.[18] Alabama Possible created the Educator Advisory Council to inform their Alabama Goes to College program. The council comprises high school teachers, counselors, career coaches, and support staff, and it informs program planning, strategy, and facilitation across the state.

Culture of Completion. Creating a culture in which students and families expect to complete financial aid applications can be accomplished by setting completion goals and creating a calendar of when students should complete key steps, sparking conversations about financial aid early in their high school careers. The California Student Aid Commission has recommended districts set a goal 5 percent higher than their previous year’s financial aid application rate and provide district-level completion rates on their Race to Submit dashboard for reference.[19] The dashboard creates both accountability and competition to move towards goals by providing transparency to the district, parents, and partner organizations. In Louisiana, to advance a calendar of key steps, the Kenner Discovery Health Sciences Academy launches financial aid work during junior year by hosting a boot camp for students and organizing parent meetings to discuss senior year milestones, postsecondary pathway options, and their student’s graduation plan.[20]

Challenges

In states with universal FAFSA policies, school, district, state agency, and nonprofit staff have shared hurdles to effective implementation. Some counselors said parents and students are reluctant to complete the forms.[21] They may be loath to share personal and financial information with the district or government generally. Some school leaders complained of insufficient capacity to implement the mandate.

The American School Counselor Association recommends a ratio of 250 students to 1 school counselor, but the national average was 376:1 for the 2023–24 school year.[22] Postsecondary planning is just one of many responsibilities these counselors are juggling. Universal FAFSA policies add multiple steps and administrative tasks to school counselors’ workload—the need to explain the requirement to students and families and helping students opt out, for example. In addition, the opt-out process has not always been standardized at the state level.[23] Consequently, LEAs must create forms and explain the process to students, and there are not consistent ways to track who has opted out.

Universal FAFSA policies add multiple steps and administrative tasks to school counselors’ workload.

Rollout of a new FAFSA during the 2023–24 school year added to these challenges. Charged by Congress in the FAFSA Simplification Act to make the form easier to complete, the US Department of Education reduced the number of questions and included a direct transfer of tax data into the form. There were numerous glitches during 2024–25, including a three-month delay of the new form’s release. As a result, completions fell by nearly 10 percent nationally.[24] There was a particular impact on students from families with mixed-immigration status, who had to wait until late February when Federal Student Aid released a workaround that allowed students with contributors who did not have Social Security numbers to complete the form.[25] Counselors said it was one of the most frustrating financial aid seasons of their careers, and students felt rushed to fill out the form when it finally became available.[26]

Most states with universal FAFSA policies gave students more time by shifting their financial aid deadlines until later. Some state college and university systems delayed their decision deadlines to give students more time to receive financial aid offers. The US Department of Education allocated funding for nonprofit organizations to support students in completing the FAFSA, with a big push over the summer of 2024.

Historically, the completion of a FAFSA strongly correlates to college enrollment.[27] However, for the 2024–25 cycle, the number of high school freshmen enrolled in college increased despite an even lower year-over-year FAFSA completion rate for high school seniors than during the pandemic.[28] This surprising anomaly requires further research before we can say whether rates will revert to those in previous FAFSA cycles.

Historically, the completion of a FAFSA strongly correlates to college enrollment.

Nonetheless, FAFSA remains critical to helping students pursue postsecondary education. Universal FAFSA policies help ensure that every eligible high school senior has the knowledge and opportunity to access financial aid. Although the challenging rollout of the FAFSA last year created an unprecedented situation, it should not deter states from efforts to promote FAFSA completion to ensure that students can gain access to federal financial aid, which keeps pathways to higher education open for so many after high school.

Alessandra Cipriani-Detres is a program associate and Elizabeth Wood is a former policy fellow at the National College Attainment Network. Anika Van Eaton is vice president of policy for uAspire.

[1] National College Attainment Network (NCAN), “National FAFSA Completion Rates for High School Seniors and Graduates,” web page.

[2] “Cost of College: The Price Tag of Higher Education and Its Effect on Enrollment” (Gallup and Lumina Foundation, 2024).

[3] Louisa Woodhouse and Bill DeBaun, “NCAN Report: In 2023, High School Seniors Left over $4 Billion on the Table in Pell Grants” (National College Attainment Network, January 2024).

[4] Steven Bahr, Dinah Sparks, and Kathleen Mulvaney Hoyer, “Why Didn’t Students Complete a Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA)? A Detailed Look,” States in Brief (National Center for Education Statistics, December 2018).

[5] National Student Clearinghouse, “Overview: Fall 2021 Enrollment Estimates,” report (2021).

[6] Brianna McGurran and Alicia Hahn, “College Tuition Inflation: Compare the Cost of College over Time,” Forbes, May 9, 2023; Maria Carrasco, “Report: The Biggest Barriers to Higher Ed Enrollment Are Cost and Lack of Financial Aid” (National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators, July 2024).

[7] Louisiana Office of Student Financial Assistance, “Universal FAFSA,” tips.

[8] National College Attainment Network, “Universal FAFSA Completion with Supports,” web page.

[9] Alessandra Cipriani-Detres, “Do Universal FAFSA Policies Prevent High School Graduation?” blog (National College Attainment Network, January 5, 2024).

[10] Bill DeBaun and Caroline Doglio, “Digging Deeper into Universal FAFSA Impacts in Four States,” National College Attainment Network, September 2022.

[11] Bill DeBaun, “FAFSA Completion Declines Nearly 5%; Nation Loses 270K FAFSAs Since 2019,” National College Attainment Network, July 19, 2021.

[12] DeBaun and Doglio, “Digging Deeper.”

[13] NCAN, “Universal FAFSA Completion with Supports.”

[14] NCAN, “#FormYourFuture.”

[15] California Student Aid Commission, “All In & Ready for FAFSA/CA Dream Act,” web page.

[16] National College Attainment Network, “Student-Level FAFSA Data Sharing Policies by State,” https://www.ncan.org/page/fafsadatasharing.

[17] Financial Aid for All, “A Pilot to Implement Universal Financial Aid Application, Completion in California,” brief (September 2023).

[18] Mireya Sandoval, “Opportunities and Challenges of Universal FAFSA” (uAspire, April 2023), https://www.uaspire.org/getattachment/40c4f21c-2240-4a58-998f-5832789338b5/Opportunities-Challenges-of-Universal-FAFSA.pdf.

[19] Financial Aid for All, “A Pilot.”

[20] Sandoval, “Opportunities and Challenges.”

[21] Sandoval, “Opportunities and Challenges.”

[22] American School Counselor Association, “School Counselor Roles and Ratios,” web page.

[23] Sandoval, “Opportunities and Challenges.”

[24] National College Attainment Network, “FAFSA Tracker,” web page.

[25] MorraLee Keller, “ED Announces FAFSA Workaround, Fix for Students from Mixed-Status Families,” National College Attainment Network, February 21, 2024.

[26] Jonathan S. Lewis and Alyssa Stefanese Yates, “Chutes and Ladders: Falling Behind and Getting Ahead with the Simplified FAFSA,” blog (Boston, MA: uAspire December 12, 2024).

[27] Bill DeBaun, “Survey Data Strengthen Association between FAFSA Completion and Enrollment,” National College Attainment Network, April 4, 2019.

[28] “Current Term Enrollment Estimates: Fall 2024,” National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, January 23, 2025.

Also In this Issue

Sustaining Gains at the Pre-K to Kindergarten Transition

By Robert C. Pianta and Christina StephensBetter alignment in policy and practice can ensure that the skill boosts from pre-K persist throughout the elementary years.

Supporting Students in the Middle Grades

By Creed Dunn, Judy Frank and Allyson MorganAcademic success, engagement, attendance, and postsecondary preparation hinge on smooth transitions at the center of K-12.

Promoting Students’ Well-Being during the Transition to High School

By Briana A. López and Aprile D. BennerAcademic success in ninth grade requires supports for healthy social and emotional development.

Prioritizing the Measures of K-12 Success That Matter Most

By Ryan ReynaState leaders can drive real system improvements by rewarding K-12 schools for helping students succeed after high school.

FAFSA as a Pathway to Postsecondary Education

By Alessandra Cipriani-Detres, Anika Van Eaton and Elizabeth WoodLearning from early adopters of universal FAFSA can help other states design and implement effective policies.

How Illinois Gets Students Ready for College and Careers

By Emily RuscaState leaders build coherent policies and frameworks to help communities guide students through their postsecondary paces.

Supporting Students with Disabilities in Transitioning to Adulthood

By Jennifer K. Migliore, Jessica Ellott, Kimberly J. Osmani and Lydia DempseyA collaborative approach can improve students’ outcomes.

i

i

i

i

i

i